I’ll be honest, I have been looking forward to this design blog post for a long time. After learning more about narrative and specifically how it is interconnected with the level design and mechanics of a game, it is time to tackle what is arguably my favorite game of all time – Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door, for the Nintendo GameCube, which can be abbreviated as TTYD.

In this post, I will explore how all traditional Mario games employ certain structures that make the games pleasing from a level design and mechanical perspective. Then, I will analyze how Nintendo expanded on the “Mario” structure already in place to create the original Paper Mario for the Nintendo 64 (PM64), and, from there, created TTYD – a game that retains this structure that makes it still feel like a “Mario” game, yet also a game that connects its structure to a multitude of rich narrative themes and characters, a combination of successes that had not been reached yet in a Mario game.

I will then compare TTYD to its potential successors that came after it, and explain why I still believe TTYD stands above them all. And then, finally, I will discuss why TTYD, the greatest Mario story ever told, still has flaws at its core.

The lens within which I intend to do this is through Christopher Alexander’s A Nature of Order, where he posits on how there are inherent patterns in architectures, games, life, etc. that, when employed and noticed, create a pleasurable feeling that things are balanced, comfortable, all right:

For the uninitiated, these patterns can be described as such [1]:

For the uninitiated, these patterns can be described as such [1]:

- Levels of Scale: We are constantly interacting with things small, medium, and big, and changes in these scales can be seen and felt.

- Strong Centers: We are interested in things, like the solar system or atoms, that are centered.

- Boundaries: Boundaries create centers, and there are also physical and thematic boundaries that need to be crossed in order for change to occur.

- Alternating Repetition: We like going back and forth, like falling/rising tension flow in a story, or checkerboard patterns. They are pleasing.

- Positive Space: There is an interplay between positive and negative space. Sometimes negative space can enhance positive space.

- Good Shape: We like shapes that are not trying to be pretty but, through their inherent purposes, make pleasing shapes, like sails catching the wind.

- Local Symmetries: Our brains are programmed to spot tiny symmetries (i.e. in our bodies, between characters in a story) that feel connected, even if, globally, they are not.

- Deep Interlock: We like the feeling that things are interconnected, that things which happened ages ago, that felt meaningless at the time, have some significance. Characters, stories, mechanics, themes, must feel connected or the feeling starts to fall apart.

- Contrast: We can perceive two things brought together in unexpected ways, or one thing (like comedy) enhancing another thing (like tragedy).

- Graded Variation: This regards things changing overtime; things we can’t spot instantaneously but when we look back at them, we realize the change that happened between now and then.

- Roughness: We don’t want characters and things that are 100% smooth, because imperfect things feel human, real, and natural in their messiness.

- Echoes: One thing echoes another, like game mechanics or characters echoing the central theme of a story.

- The Void: Oftentimes the most important things are in empty spaces.

- Inner Calm: We are not given all the information at once, so that emergent complexities can come out through natural tension.

- Not-Separateness: We like the feeling that pieces, even if they are physically separate, are not, and that if you take one piece away, the other suffers. The world is connected.

The Mario Structure

Traditional Mario games, from the classic platformers to the early 3D Mario games such as Super Mario 64 (SM64), actually do a fairly decent job in employing these patterns to create aesthetically pleasing “Mario” structures:

1 – Levels of Scale: This is not just in Mario literally changing size in most games, but this is also true structurally as well, in which you are able to interact with all three levels of scale:

-

-

- Small: Coins, items, enemies, in-level things

- Medium: The levels themselves that must be completed

- Big: The big map, the worlds you go through. Not all games have maps, but most, like Super Mario World (SMW) or Super Mario Bros. 3 (SMB3), indeed do, allowing you to track your progress.

-

Three levels of scale as seen in Super Mario World

- 2 – Strong Centers: The platformers are often devoid of this (outside of maybe Mario being your center, which is a reach), with the levels simply stacking up on each other as you go through the world, from point A to point B.

But with SM64, Nintendo improved on this with Peach’s Castle, proving that a strong center can work with a Mario experience that you keep coming back to and which serves as your hub.

3 – Boundaries: In all Mario games, the game is divided into worlds that you must complete in order to move on to the next one, and each world typically has a singular aesthetic that binds it to itself.

Worlds 2, 4, and 6 (respectively) in SMB3

SM64 also has numerical boundaries of stars you need to collect in order to unlock new worlds, and Peach’s Castle has literal photo boundaries that you need to jump through in order to enter levels.

4 – Alternating Repetition: Platformer levels that just build on each other are actually not the best at this, considering you’re just playing levels which don’t necessarily repeat. With SM64, you can argue that there is a light repetition of needing to at least set foot in Peach’s Castle between completing one of the missions in the levels. Additionally, certain elements, like mountain regions, repeat overtime between levels – Course 4 is Cool, Cool Mountain (left below) and Course 12 is Tall, Tall Mountain (right below).

Because this aspect is sparse, maybe Nintendo was experimenting with this aspect in these earlier games. But this aspect is less noticeable than some of the other patterns.

5 – Positive Space: The Mario aesthetic is brilliant at this, and one of the reasons it is so nice to look at. Mario, the collectible items, his enemies, the coins you collect, etc. are often drawn using hot, red colors that contrast vs. the environments that are cool colors like blues or greens, creating Positive/Negative space. Mario himself, with his reds, pops out a lot.

6 – Good Shape: Some of the Mario maps, particularly SMW, create a good shape. Mario does so too when he puts on the different suits, creating new lines and angles in himself. These new suits are meant to give Mario new abilities, but also create interesting, contrasting shapes that complement these abilities. Keep in mind, these abilities are mechanically based and less from a character and thematic level.

7 – Local Symmetries: Again, the platformer style doesn’t lend itself much to symmetries. It can be argued that you encounter similar types of levels in each world at specific places (you often are traversing left to right with an enemy castle on the far right, repeatedly), and that Peach’s Castle in SM64 is largely symmetrical from an overworld perspective. From a character perspective, the only characters often symmetrical to each other are the enemies who are sometimes mirrors (like Red vs. Green Koopas), and Mario vs. Luigi. These symmetries are often more aesthetic and not from characterization.

8 – Deep Interlock: This unfortunately is an area where Mario games often suffer; there’s rarely a case of a thing or item you didn’t think was important becoming important later. In many ways, there are just not enough elements because everything is simple in traditional Mario. Worlds are bounded and singular, characters don’t have arcs, and there really isn’t a story for mechanics to enhance.

9 – Contrast: There is some contrast in the world level structure, which is effective. Particularly in the classic platformers, there is contrast between the island, grassland, desert, lava, forest, pipe, and sky worlds (among others), with gorgeous aesthetics for each one that contrast one with the other.

Just looking at the environment on your screen will cue a naive gamer into what world is being played.

10 – Graded Variation: This works in Mario on a pure difficulty-ramp perspective, as the levels are designed such that they become harder as the worlds progress. However, there’s little seen of the world at large actually changing, and YOUR abilities don’t advance or change much beyond the initial learning of them. You learn your jumping and running abilities fairly early, and then outside of a handful of new suits that may get introduced (also usually early), there is not much of this.

11 – Roughness: Roughness arguably comes from the weirdness of the villain characters and how some of them act through their physical mannerisms. However, on a character level, Mario characters are typically EXTREMELY smooth, which makes the games simple and accessible, but also makes them feel less mature.

12 – Echoes: Echoes can come from certain levels or abilities (you become a frog in the water level, for example). The enemies often echo the environment as well. These echoes exist outside of character and narrative, though, as there isn’t much of a theme in traditional Mario games.

13 – The Void: Bowser’s Castle usually takes up some nice space on game maps, with a lot of empty room around it.

Still, this is usually only seen at the end of games, so it is not set up as well as it could be. You can argue that Peach is a metaphorical Void that is missing, but you rarely see the effects of her being missing. This is a “maybe” in SM64, because the game starts with her inviting you for tea, and then when you arrive, she is absent, which creates this feeling of dread and worry (also, it’s Peach’s Castle with no Peach for the entire game).

14 – Inner Calm: Well, there’s a calmness in Mario and complexity, emergent-wise, in the Level Design, but because you aren’t unlocking many new abilities or lore, there isn’t a whole lot of emergent complexity.

15 – Not-Separateness: Again, this is a problem in Mario games, even in SM64, because all of the levels feel separate. This is the Mushroom Kingdom; but it doesn’t feel like a real, full, lived-in place. Characters inherently don’t feel connected, neither physically nor emotionally.

So, we have a Mario structure that is expertly used in creating scalable structures and complexities in the levels themselves, but a structure that is, basically, devoid of narrative and emotional connections.

Nintendo eventually tried its hand at Mario RPGs, and the genre alone

lends itself to much more complex narratives and structures. After experimenting with Super Mario RPG (see below), Nintendo released the original Paper Mario.

Note: I played SMRPG a long time after already playing the Paper Mario series and the Mario and Luigi series, so my knowledge of these games as not as informed by SMRPG as many others. However, I saw SMRPG as a wonderful game in its own right with an amazing plot, but one that didn’t use the Mario structure as strongly as its successors. This is why I see it as an “RPG experiment” that Nintendo practiced with before merging it with more known Mario structures. See the section “Challengers to Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door” for more details about this.

From this point on, I am only speaking about PM64 and later TTYD. So, from here on out, be aware of spoilers for both games.

Porting the Mario Structure to the RPG: The Original Paper Mario

Through this game, Nintendo managed to port the Mario structure seen in platformers and 3D into a grander scale, incorporating some of the elements the classics were weaker on, to make the world more satisfying. In this original, the story is worth mentioning only somewhat, as it is not wholly complex. The plot is not nearly as complex as Super Mario RPG, but that is not the point of Paper Mario. The story is meant to exist in a similar vein to a traditional Mario adventure, but expanded to incorporate more of the world and the core characters’ effects on it. It shows Nintendo’s ability at taking a simple, emotional theme and connecting it across its mechanics and characters to create beautiful results.

For the uninitiated, in Paper Mario, Bowser kidnaps the Star Spirits and steals their powerful Star Rod. This boosts his power, allowing him to capture Peach’s Castle by raising it high into the sky. Bowser is then powerful enough to defeat Mario in single combat. Mario must then traverse the Mushroom Kingdom to retrieve the Star Spirits, held captive by Bowser’s minions, and eventually return to the skies to fight Bowser once more.

1 – Levels of Scale: Mario doesn’t change size in PM64, but the game makes up for it through its structure. Firstly, there are literally three different types of game spaces for you to interact with:

-

-

-

- Small: The battle screen, where you fight enemies in turn-based gameplay.

- Medium: In-world, where you traverse the Mushroom Kingdom and solve puzzles and interact with characters.

- Big: The map, which you can view whenever you’d like.

-

-

-

- And, like the established Mario structure, there are small items/badges/coins you can use to affect you, medium characters and enemies that you interact with, and the larger, big-picture structure that you are traversing, which carries more narrative weight this time.

2 – Strong Centers: The game is all about its strong center. Toad Town acts as a hub throughout the game that you continually return to and is full of life, shops to visit, and NPCs to chat with. Additionally, Peach’s Castle (which has been uprooted) acts a subtle Strong Center on its own.

3 – Boundaries: Firstly, during some game moments, the game employs actual boundaries. This is similar a bit to SM64 in unlocking more of the physical game space as you progress through it. (Example: At first there is debris that prevents you from exploring the southern half of Toad Town, but it is removed after Chapter 1. This becomes very satisfying and feels like you opened up the city.)

You also can see some boundaries on the map so then it feels satisfying when you cross them (i.e. getting to go to Lavalava Island in Chapter 5 after viewing it on the map up until this point).

Plus, biggest of all (which turns Peach’s Castle into a strong center) is the boundary between you and the castle. The game starts off IN-CASTLE with Mario visiting Peach, so in your mind, Peach’s Castle feels like the center even though Toad Town is the game center.

You’re then thrown from it and Peach’s Castle is raised high into the sky by Bowser, with you needing to find a way back, a crossing-the-boundary task that initially feels impossible.

When you actually do, when you’ve made it back to Peach’s Castle at the end of Chapter 8 (where you were at the beginning and where you’ve been playing as Peach multiple times), it feels like you have finally returned to where you’re meant to be. It feels glorious.

Lastly, of course, the Mario structure itself is built on boundaries of levels, and PM64 utilizes this with the chapters. It’s a bigger world and an interconnected Mushroom Kingdom, but the boundaries are still there with each chapter feeling like a stand-alone part of the story with a mission to complete.

4 – Alternating Repetition: Ah, NOW it has it. Each chapter typically has an “overworld” that also has some sort of “village” or hub of NPCs, followed by a “dungeon”:

-

-

- Chapter 1: Pleasant Path (overworld), Koopa Village (hub), Koopa Bros. Fortress (dungeon)

- Chapter 2: Mt. Rugged/Dry Dry Desert (overworld), Dry Dry Outpost (hub), Dry Dry Ruins (dungeon)

- Chapter 3: Forever Forest/Gusty Gulch (overworld), Boo’s Mansion (hub), Tubba Blubba’s Castle (dungeon)

- Chapter 4: Toad Town (overworld/hub), Shy Guy’s Toy Box (dungeon)

- Chapter 5: Lavalava Island (overworld), Yoshi’s Village (hub), Mt. Lavalava (dungeon)

- Chapter 6: Flower Fields (overworld/hub), Cloudy Climb (dungeon)

- Chapter 7: Shiver City/Starborn Valley (hubs), Shiver Mountain (overworld), Crystal Palace (dungeon)

- Chapter 8: Star Haven (hub), Bowser’s Castle (overworld), Peach’s Castle (dungeon)

-

Notice how as the chapters progress, the game begins to play with this alternating repetition to keep you on your toes as to what to expect next. The game uses Toad Town, the de facto center of the entire game, as the “hub” for a chapter as well. The last two chapters start out with you in the “safe place” with NPCs before sending you off on your quest. You get the idea.

There is also a grander scale of Mario returning to Toad Town in-between

levels, which creates a pattern of Worlds / Toad Town / Worlds / Toad Town (with a playing-as-Peach level thrown in-between there for good measure). This a similar repetition to the Levels / Peach’s Castle / Levels from SM64, but because you spend more time in Toad Town in this game compared to Peach’s Castle from SM64, this pattern stays with you more strongly.

Also, if you are so inclined, there are different sidequests that become unlockable with each chapter you complete, so these stack onto your feeling of repeating them with each iteration. For example, you unlock three more of Koopa Koot’s missions after each chapter, so, before leaping into the next world, you can choose to complete them as part of an interlude, and then your mind expects to complete them as part of the next iteration. This is also true with unlocking new badges at Rowf’s Badge Shop, and delivering Parakarry’s letters, among others.

5 – Positive Space: Again, the Mario aesthetic with paper is wonderful and creates LITERAL contrast with the paper lines on characters and objects, which make them stand out and pop.

Also, Bowser is at his most menacing in this game, and there’s an energy about him that creates this positive space whenever he’s on screen (because, well, he basically murders you in the first scene, which makes you see him as a much larger threat than usual). This is reinforced by the aesthetic point that when he is glowing, he is at his most strong. So, here, the aesthetics of Positive Space are reinforcing the deeper Positive Space of Bowser’s characterization.

There is also a contrast of seeing the shadowy, see-through Star Spirits that appear beside you at the beginning BECOMING positive space as you save more and more of them. Again, Positive Space reinforcing the central plotline and theme.

6 – Good Shape: The world map, for one, is great to look at, and it’s great to see your trails of the places you’ve visited creating dotted lines across the Mushroom Kingdom.

There are also shapes with the dishes that Tayce T. cooks for you- you want to keep making the dishes to see the different shapes of what they look like, but the interesting shapes they make are secondary, as their purposes are to help heal you in different ways.

7 – Local Symmetries: You encounter similar types of enemies in certain worlds (just like in classic Mario), and then certain enemies (like Gloombas or Hyper Goombas) repeat in terms of style, which create symmetries that lead back to them. So, as you’re fighting a Hyper Goomba in Chapter 3, you’re thinking about that time you fought an ordinary Goomba in the prologue and how this current experience is different.

There are also local symmetries with how the items in-game connect with each other (Mushroom vs. Super Mushroom vs. Ultra Mushroom, etc.), which leaves you thinking about how their different abilities relate.

8 – Deep Interlock: In-game, this happens a lot, as within a chapter, you’ll find a certain item or there will be some mystery early on that gets resolved later. For instance, in Chapter 6, you get various items from the various flowers and only figure out how to use them by talking to other flowers and realizing which flower needs which item. Most mysteries are self-contained within each chapter, however.

There are also larger-scale connections with Kolorado (returning as comic relief several times in the story) and Jr. Troopa (a character whom you fight as your first mini-boss and who returns for revenge a total of five more random times). Aside from these, however, there’s less of an interconnected narrative that you feel. In-game, you’ll get introduced to new mechanics AND partners as the story and worlds progress. But less globally.

9 – Contrast – There is the same wonderful contrast that traditional Mario has, with the different vivid worlds.

Thematically and mechanically, each level is more or less the patterned overworld + dungeon in which you have to figure out who is behind some sort of mystery, and why/how to defeat them. The contrast is in the details, and, aesthetically, it’s brilliant.

The yellows of the desert vs. the purple of Forever Forest vs. the blue-green of Yoshi’s Island vs. the shining white of Shiver City vs. the grey-orange of Bowser’s Castle make them distinct.

Also, unlike traditional Mario, the game employs dialogue that acts as a contrast for the rest of the game (listening to NPCs is contrasted with running around in the overworld). The comedic dialogue between characters typically contrasts with the seriousness of the subject matter, but, at least with PM64, the subject matter is not completely world-ending or anything.

10 – Graded Variation – Here we go: You feel the world at large changing more (i.e the difficulty ramps up with types of enemies, you unlock more abilities / more badges / partners / more ways to fight, etc.)

You are unlocking all these things and adding abilities or people to your inventory, so it feels like you are changing.

Toad Town changes as well. If you spend the time talking with people, you see people’s opinions of Peach’s absence changing more, with some maintaining their wishes for her return, with others giving up hope, and others moving on to small issues in their own lives, such as longing for Toad romances.

If you return to your house and interact with Luigi, you’ll see that he also changes, with his opinions of you going from “take me with you” to “you’re never gonna take me with you” to “I wish you luck regardless.”

What’s interesting is that all these changes are triggered by boundary checkpoints of completing a chapter. Once you do, time passes and characters’ opinions change. You feel the sense of time in this game, which follows over to its successor.

11 – Roughness – It feels very fresh to see some ROUGHNESS (as in, character and different aesthetics) added to traditional Mario characters like Toads, Goombas, Koopas, and others. You can see this in the Mushroom Kingdom denizens, like the different Toads are of different colors, wearing different types of clothing, or have different kinds of hairstyles. But most especially, you see this with your partners.

Each one has a unique aesthetic, like Goombario having a blue hat to make him stand out from a traditional Goomba, or Bombette being a pink Bob-omb. The game takes the traditional Mario enemy and tweaks them to make them your friends. Some of their personalities are more fleshed out then others, but aesthetically, absolutely yes.

This applies to Peach as well – instead of a pure damsel in distress, she’s out there causing mischief and trying to help, finding out information for you and potential boss weaknesses in between chapters.

12 – Echoes – Each party member echoes the environment/chapter you find him/her in. For example, you meet Kooper in the Chapter 1 grassland area that is full of Koopas, so it makes sense that you would meet him here. You meet Sushie, a Cheep Cheep fish, in the water/island area, so it makes sense that you would meet her here. This goes along with there being certain items/enemies/characters echoing traditional Mario games.

The story (needing to save Peach to restore her absence to Toad Town mirrored by needing to save the Star Spirits to give people hope) is very, very simple, but it is built by the fact that at the beginning, you, like, basically almost die. So, the game is built on a foundation of hopelessness, echoed both through your journey, the loss of the Star Spirits, and Peach’s abduction.

As you get stronger, you begin to feel more hopeful. You’re saving more Star Spirits, and Peach is unlocking new locations in her castle. There is a literal montage effect of finishing a chapter and saving a Star Spirit echoed by a Peach chapter to see how she changed as well.

The point is – unlike traditional Mario games that are more or less just about Mario and Peach, in Paper Mario you feel the effects of this conflict on the world. The world needs hope.

And yeah – you building yourself up and getting more of the world behind you bring hope. Once you rescue Peach and the Star Spirits and defeat Bowser, the story ends with the world parading, and you looking at the stars with Peach (a.k.a. one of the most romantic moments between Mario and Peach in a game), with everything echoing each other.

The music of the game also provides echoes. There are battle themes, leitmotifs for the Star Spirits which come on every time you save one, and Bowser’s theme has never felt more sinister.

13 – The Void – Again, there is a LITERAL VOID of Peach’s Castle being missing which connects back to all the echoes of it listed above. Also the void of the shadowy Star Spirits that you see at the beginning makes you feel their absence in Star Haven.

And in terms of level design, the game indeed employs the boss-battle-in-a-big-room, or dungeon-in-the-middle-of-nowhere style of design as well.

Lastly, the very end of the campaign, you arrive at Peach’s Castle after fighting your way through Bowser’s Castle in Chapter 8. You’ve finally arrived that the space where you’ve played as Peach and navigated through a bunch of enemies, but the entire castle is empty. And you’re like, “oh my – Bowser is here somewhere. Time for the final battle.”

14 – Inner Calm – There is emergent complexity in the gameplay as you unlock new party members, hammers/boots, badges, and other bonuses that give yourself more STUFF to work with in-battle. There is less emergent complexity for the sake of narrative though. The stakes are established early, and from there, the chapters, more or less, stand alone until the climax.

15 – Non-separateness: This aspect is perfect here, as the worlds feel connected. Mario games are typically about saving the princess, but here you actually see what her absence is doing to her subjects. There is also the fact that Parakarry’s letters, Koopa Koot’s missions, and other sidequests between characters make you realize that all these NPCs have actual relationships with each other and backstories and histories.

So, as we can see, the original Paper Mario expanded the Mario structure out into a 3D RPG, utilized a powerfully simple paper aesthetic, and employed more of these patterns to create a very pleasing experience. But, as seen as well, this experience is largely constrained to the chapter-by-chapter level.

Characters usually are not crossing over across chapters (except for Kolorado and Jr. Troopa) and some of the complexities (outside of the initial hook/stakes of the game) are bounded by their chapters.

The narrative itself is very simplistic. Powerful, yes, but not reinforced as much as it could be during the middle, nitty-gritty parts of the game. The beginning reinforces the end and there are individual chapters to get there (which are more obstacles than emotional keystones). The party members, as well, while a breath of air to see vis-a-vis new roughness added to iconic Mushroom Kingdom denizens, are fairly baseline.

Paper Mario and The Thousand-Year Door:

When an Established Design Structure is Extended to Narrative

Four years later, however, Nintendo released the sequel, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door, and took the structure that worked with the original PM64, and expanded it. Only this time, they extended the structure to create an emergently complex narrative reinforced by the characters and mechanics over the course of the game. Let’s begin:

For the uninitiated, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door begins with the lore that, a thousand years ago, there was a prosperous town that was destroyed by some sort of ancient cataclysm. This town fell underground and was entombed behind the mythical Thousand-Year Door, magically kept shut by the seven Crystal Stars. Legend has it that if you unite the Crystal Stars, you can open the Door and obtain whatever lies beyond it, be it an ancient treasure, a weapon, or worse.

The rugged town of Rogueport was built above the Door, and, during a vacation, Peach is able to unlock an ancient chest (because she is pure of heart) that contains the Magical Map that leads to the Crystal Stars. Peach sends the Map to Mario, asking him to come with her on a treasure hunt, but when he arrives in Rogueport, she is gone. And shady creatures, calling themselves the X-Nauts, are asking questions about the Map.

Mario is tasked with using the Map to find the seven Crystal Stars before the X-Nauts and other baddies do, figure out where Peach is, and solve the mystery of what lies beyond the Thousand-Year Door.

In the end, it is revealed that an ancient demon, the Shadow Queen, lies beyond the Door, and that the X-Nauts (who kidnapped Peach this time) plan to use her body as a vessel to awaken the demon.

1 – Levels of Scale: This is kept consistent. The game uses the same types of screens and scale structure as its predecessor.

2 – Strong Centers: Similar to its predecessor, TTYD has two strong centers: Rogueport AND The Thousand-Year Door. The question of where Peach is remains a mystery for the majority of the narrative, as does the question of what is behind the Door. Rogueport is your hub that your return to in between chapters, but the Door, bounded by the drawings of the Crystal Stars and set up initially by its lore, becomes the more important Center over time, as does its central mystery of what is behind it.

So, like PM64, you have your Game Strong Center and your Thematic Strong Center. In PM64, the theme was represented by the absence of Peach’s Castle. In TTYD, the theme is represented by the Thousand-Year Door itself.

3 – Boundaries: Throughout the game, the Thousand-Year Door prevents you from entering the final world. In the pre-game prologue, the game introduces the mystery of the Door being created, so your mind is tuned in from the beginning of wanting to see what’s behind it.

There are boundaries to each chapter that you need to unlock with the Crystal Stars. TTYD is actually weaker here compared to PM64, thematically, because in PM64, the boundaries were there to reinforce the Mario/Peach dynamic more. But TTYD game still has them. Same with needing to complete different chapters (plus playing-as-Peach interludes and playing-as-Bowser interludes) to cross boundaries of unlocking more of the world and its lore.

4 – Alternating Repetition: This is employed just like predecessor. You have Worlds / Rogueport / Worlds / Rogueport (with Peach levels and Bowser levels in between). And, like its predecessor, TTYD employs the overworld/hub/dungeon dynamic as well:

-

-

- Chapter 1: Petal Meadows (overworld), Petalburg (hub), Hooktail Castle (dungeon)

- Chapter 2: Boggly Woods (overworld), The Great Boggly Tree (hub/dungeon)

- Chapter 3: Glitzville (overworld/hub/dungeon)

- Chapter 4: Twilight Town (hub), Twilight Trail (overworld), Creepy Steeple (dungeon)

- Chapter 5: Keelhaul Key (overworld/hub), Pirate’s Grotto (dungeon)

- Chapter 6: Excess Express/Poshley Heights (hubs), Riverside Station (overworld)

- Chapter 7: Fahr Outpost (hub), The Moon (overworld), X-Naut Fortress (dungeon)

- Chapter 8: Palace of Shadow (dungeon)

-

However, unlike its predecessor, the game actually “breaks” the pattern more of world/dungeon to keep you on your toes, which pays dividends later on. In PM64, outside of Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, once you reach the dungeon, you don’t leave it.

Whereas in TTYD, you are often sent back out into the overworld to solve some mystery even after reaching the dungeon (as is the case with Chapters 4 and 5, revealing that the dungeon wasn’t the core of the chapter story), or the overworld/hub/dungeon pairing is messed with completely. I like to believe that, in the first two Chapters, TTYD patterned itself very much after its predecessor so you’d start to think the entire game would repeat PM64’s patterns, but then started to spread its wings to the point where you never knew what would happen next.

5 – Positive Space: The game maintains the Paper aesthetic for positive space. Also, Rogueport, which is a grimy, run-down location, is contrasted by the Door itself, which is magical and mystical in comparison. The Crystal Stars feel like they come from a different world…

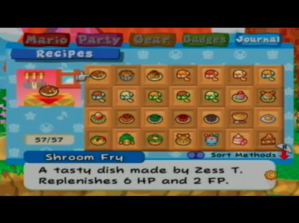

6 – Good Shape: The game employs a similar mechanic like PM64 with Zess T. making new dishes out of items you find. But MOST OF ALL, the game introduces the ability for YOU TO CHANGE. The game employs the aesthetic of the game (paper), enabling you to be able to turn into paper things like planes and tubes and boats to get through puzzle blocks, but this also makes a good shape and calls back to traditional Mario games of you being able to change size and shape (upon obtaining new suits) to be able to do new things.

7 – Local Symmetries: Let’s be honest, for someone having played the original PM64, it is enjoyable to see symmetries across-game to make you think when and how it will break them (i.e. TTYD’s Chapter 1 environment mimics PM64’s, as do the first two partners you meet in the game). This makes it a good sequel, as there are thematic callbacks to the original, even if you rarely see characters from the original.

Chapter 1 of TTYD (right) mirrors Chapter 1 of PM64 (left)

But the game also has symmetries (more actually) between enemies, items, badges, etc. There is a literal challenge of tattling on lots of enemies to put them in your Tattle Log, and then you get to literally see the symmetries between the enemies you fought. Same goes for the desire to cook more and more dishes to see them appear in your Recipe book. As you unlock more and more, it becomes more satisfying as you approach a feeling of completeness.

There are also symmetries across character (i.e. the Chapter 1 boss Hooktail turns out to be one of three siblings, just like the mini-boss Shadow Sirens), which, cleverly, connect to the greater story this time (see further below).

8 – Deep Interlock: The game maintains the in-chapter mysteries of things you find at the beginning becoming important later similar to PM64.

But this time, characters who appear early on end up being revealed later as being more important and NOT just stand-alone unlike in the original PM64. Let’s see:

-

-

- Chapter 1: In addition to Ms. Mowz (who later becomes an optional party member) being introduced, Hooktail is the chapter boss, who is later revealed to be one of three dragons in the Shadow Queen’s employ.

- Chapter 2: The Shadow Sirens are introduced and return multiple times later on in the story. Also, the X-Nauts and Lord Crump (and by extension Magnus von Grapple) are formally introduced as enemies, and return later in Chapters 5 and 7.

- Chapter 3: The chapter boss, Grubba, is using the Crystal Star’s power for evil, but doesn’t return after he is defeated (see below).

- Chapter 4: The ghostly boss, Doopliss, returns later as a villain again in Chapter 8, and is also is a catalyst for Vivian’s arc, who formally rejects her Shadow Siren sisters to join you in your quest.

- Chapter 5: The pirate boss Cortez is used as a decoy villain in order to reintroduce Crump as a true villain. Cortez later becomes your friend to ferry you back and forth from Keelhaul Key and Rogueport.

- Chapter 6: The perpetrator in the mystery onboard the Excess Express turns out to be Doopliss in disguise, and later the Shadow Sirens re-appear in this chapter, dangerously close to beating you to the Crystal Star’s location.

- Chapter 7: You return to the location where Peach was being held, fight Crump for the last time, and finally meet TEC, the computer that has been helping Peach all game.

- Chapter 8: This final chapter has a lot of payoffs. You fight Gloomtail, one of Hooktail’s siblings, then the Shadow Sirens and Doopliss again. Then you finally meet Grodus, who is the leader of the X-Nauts and the main villain up until this point. Then Bowser crashes the party and it is teased that maybe he could be the final villain, just like PM64, even though he has been one step behind you the entire game, but he is defeated. Then, the mystery is completed as the Shadow Queen is awakened and you are forced to fight to the sake of the world. Plot twist: the Shadow Siren Beldam is turns out to be the one who engineered the entire plot to be in motion by baiting Peach to find the Map.

-

And what’s more, a larger mystery can be slowly unraveled to see how and why these events are important (i.e. what is going to happen to Peach, why do the X-Nauts have her, etc.). Most of this information is unraveled during the Peach interludes.

9 – Contrast: Contrast in-world starts off with different aesthetics but then shifts to being more about the type of place you are in vs. the color of it. You can still see contrast in people like in original PM64, but in TTYD it goes more beyond aesthetics. The denizens of PM64 are often similar, all average-Joe characters going through life, just they are different species. In TTYD, however, there are entirely different life-moods in these NPCs!!

Take the Twilight Town people that are dour just because that’s where they live, or the machismo types you meet in the Glitz Pit, or the Poshley Heights people that are visibly snobby.

Comedic dialogue is employed in this game just like the original, which endears you to the characters. But the subject matter on the broad scale is inherently more serious, so this contrast becomes more vivid.

10 – Graded Variation – You definitely feel like things are changing overtime, particularly in terms of TEC’s growing love for Peach, and in certain characters. Compared to PM64, there is less graded changes amongst the expanded world, but the characters that do change and evolve do so even more deeply than those in the original (more on this in the next few sections).

11 – Roughness – This is where TTYD arguably shines the most. Firstly, Rogueport feels even more personable than Toad Town (in a way) because everyone is a rugged type and oftentimes angry at the world. This is something that’s rare in a Mario game – realism!

For example, Zess T. cooks for you, but unlike Tayce T. from PM64 who is uber-sweet, Zess T. calls you names and insults you. Initially, you’re like “whoa, Mario characters aren’t supposed to be this way!”

There are characters in Rogueport who literally complain about not being able to find work. And through the Trouble Center, these characters will place requests that you can help them with. Through this, you can learn more about them (and there is incentive because you gets coins and other goodies for doing so).

And then – of course – there is the party. Every party member (or at least most of them) not only has a unique aesthetic but a unique personality that changes. PM64 was very much about putting aesthetic twists on old enemies. TTYD does this somewhat too (i.e. Goombella, Ms. Mowz, Yoshi), but each party member HAS a unique backstory or personality.

For example, whereas Kooper in original PM64 is your standard Mario superfan, Koops in TTYD is a scared, fragile individual that needs to overcome his fears, save his dad, and become worthy of his girlfriend, Koopie Koo. See the table below for more comparisons of the partners in TTYD vs. their closest counterparts in the original PM64.

Some TTYD party members are direct mirrors to their original party members’ abilities and species. But when compared more in terms of personality, TTYD has the deeper roster. It is telling that the only partner that has no direct mirror in TTYD is the original’s Parakarry, whom is your most direct link to the NPCs in that game. This illustrates how the original placed more of a focus on an expanded world with more NPCs to connect to you, whereas TTYD places more of a focus on deeper characterization.

Now, on to the the villains: Bowser’s menace is sacrificed for the sake of comedy. I personally prefer the more menacing version of Bowser from the original, because he was still funny sometimes, like with his diary about Peach, but because he wins the game’s open fight, he’s still menacing, whereas in this one, he’s more or less a joke. Yet, it works for this game because Bowser’s plotline (him being one step behind you the whole time) reinforces the dialogue and the tone.

Regarding the story’s real villains, Grodus is your standard villain who wants to conquer the lands and wants power for the sake of power (but he’s not Bowser so it’s initially intriguing on a meta-scale). Grodus has far more in common with the main villain from Super Mario RPG, Smithy, as the leader of a mechanized army from another world invading Mario’s world, wrecking havoc on its denizens, and wanting to collect star-shaped MacGuffins to further his plans. However, whereas Smithy’s malice stops there, Grodus has additional depth because you see more of him over the course of the game, and his plans are meant to awaken an even worse villain.

You see how manipulative and cruel Grodus is, and how he enjoys causing pain to his minions. So Grodus is already built up as a truly evil person. It is thus a genuine twist that Grodus isn’t the final villain (as the encounter at his lair, where Peach was being held, is in Chapter 7). The Shadow Queen is the main villain. And she kills Grodus before the final battle. The fact that Grodus, whom we recognize as evil, is dispatched of so quickly foretells the true power of the Shadow Queen.

Even though the villains aren’t especially dynamic (they do not have a ton of hidden depth), they are memorable for their cruelty, their affects on the world, and the central mystery that surrounds them, particularly the Shadow Queen.

Additionally, talking about Roughness, take TEC, the computer at the X-Naut base, who gets a full-blown, full-game character arc as he falls in love with Peach. It’s an archetypal one (the computer who is “bad” learns how to love), but the actual fact of seeing a full-game character arc in a Mario game is very unique.

Plus, he DIES. Grodus shuts him down before Chapter 7, and you genuinely feel it, especially with Peach horrified at her friend being terminated. At this point, you’ve come to love this computer. He holds on long enough to speak to Mario at the end of the following chapter, but then seemingly dies.

Note: In the denoument, it is revealed that Grodus and TEC actually lived, which is a shame as it undoes a lot of this darkness. The denoument is one of the few true flaws of TTYD, but more on that later.

Lastly, in terms of Roughness, each of these characters begin to reinforce an aspect of MARIO’s personality. I’ll get to this more, but Mario doesn’t really have a personality. However, over the course of the game, different characters (even ordinary NPCs like Chapter 3’s KP Koopa, “King K”) begin to acknowledge Mario as this “strong, silent type” almost as if Nintendo was aware of how devoid of a personality Mario has and turned it into a running gag.

The fact that Mario is given multiple nicknames (such as Marty-o, The Great Gonzales, even “Luigi”) showcase how he can be anyone. But this is most showcased through many of his partners:

- Goombella: She appreciates you for helping her (and you see your abilities as a hero reinforced on a smaller scale, outside of grand Peach-rescuing)

- Koops: He acknowledges that you give him courage

- Flurrie: She flirts with you… a lot

- Yoshi: You hatched him and named him, and he’s the one most like to “bro” out with you.

- Vivian: She literally switches sides because you’re kind to her. She is the partner that comes to the closest to actually truly loving Mario (and done for real, outside of standard Peach-rescuing, which grounds you, the player, into it)

- Bobbery: He has less of a personal connection to you, but you’re aware that you helped bring him back from the brink.

- Ms. Mowz: Flirts with you and appears a lot before joining the party, but it’s more one-note than the others and less grounded. (NOTE: If Goombella shows friend love, Flurrie shows physical love, and Vivian shows emotional love connected to Mario, Ms. Mowz is like an amalgam of all of them that is not as specific and not as connected. However, though, she is an extra, optional party member, so therefore it is likely the game was designed so that these personality connections wouldn’t be sacrificed if you didn’t find her as a party member.)

12 – Echoes: TTYD shines here as well. Party members echo their environment less because, taken as a whole, TTYD is less about its overworld and more about the narrative, so characters and mechanics echo the narrative more than the original.

The original has the stronger beginning, no question, but TTYD builds upon the central mystery more and more overtime. If the original is about finding hope and belief again, the sequel is the journey to ward off darkness.

Everywhere you go, characters you encounter are often broken, injured, or fragile people and through actions find their way back to life. Like the original, this is a simple theme, but it is reinforced over and over.

For the case of TEC or Vivian, they are “Bad” characters who find redemption.

Bobbery is on the brink (presumably of suicide, which is unheard of in a Mario game), but learns to live again through his “one last adventure” with Mario.

Additionally, I mentioned above that Chapter 3 doesn’t introduce a character that “returns” to impact the central mystery, but it actually does – thematically.

The Crystal Stars represent power, and the ability to do great things, but up until this point, we’ve only seen them either, well, lost in Hooktail’s stomach or used to power machinery. Through Macho Grubba, we learn how the Crystal Stars can CORRUPT a person’s mind and lead them directly to doing evil things (there is a subplot in Chapter 3 where the villain, later revealed to be Grubba, is literally sucking the power (i.e. life) out of retired fighters, including King K, who is your friend). So, thematically, Chapter 3 echoes the central theme of what happens if darkness wins.

Then, in Chapter 4, this question of warding of darkness is directly put into the physical realm when the main villain STEALS your body and turns you into a shadow that you have to fight out of by learning the name of your tormentor.

Of course, even in this state, simply doing something nice for Vivian allows her to see your good heart and then she agrees to help you. Again, this reinforces the theme that the “inner light” (which both Vivian and, obviously you, have) is more important than the outside.

This is also “reinforced by mechanics,” as losing your partners and being alone FEELS alone because your abilities are stripped.

There are echoes of darkness all throughout the game. Enemies have dark echoes of them, often found in the Pit of 100 Trials, which gets darker and darker the deeper you go (AND HARDER, which again is an example of the game mechanics reinforcing the theme). This is then tied into the main plot when it is revealed that, 1000 years ago, the Shadow Queen threw her prisoners or enemies into the Pit.

Example: Gloomtail and Bonetail (right) are dark echoes of Hooktail (left)

And what does the central mystery turn out to be? Grodus captured Peach in order to use her as a vessel for the Shadow Queen to embody. So, Peach, who is described in the very first scene of the story as the one “most pure of heart” and the one who enabled a computer to find love, is going to be used as a vessel for darkness that you have to save.

So, at the end, you’re indeed fighting for the fate of light in the world (literally; at this point the sky gets covered in darkness), but also metaphorically by fighting to save Peach.

So, like the original, the game is SMARTLY using Peach as an echo for the theme, which is one of my favorite aspects of these games. In the original, her absence is felt by all of her subjects and you have to restore that balance. In TTYD, she is meant to be “light” incarnate. So, in both games, you’re not saving the damsel in distress, you are saving the IDEAL of the theme.

And because the characters are inherently rougher, there is much more of a tension of finding light within them. So, at the end, when the characters need to give Mario their support during his final fight against the Shadow Queen and do so by calling out through the Crystal Stars, you feel it. Like, “Hey, if these inherently grouchy/pompous/rough characters have found belief in this cause, then so can I.”

And who is the last one to give you support that breaks the Shadow Queen’s defenses, if ever briefly? Peach, of course.

It’s an age-old story: light vs. dark. But the mechanics and narrative are reinforcing it at every turn.

Oh, yeah. And the music… is… amazing. Each track reinforces its environment wonderfully, be it the fighting style of the Glitz Pit or the moodiness of Twilight Town. The music can range from melancholic, like the track Sadness and Happiness that plays during a handful of emotional moments like Bobbery’s backstory, to incredibly dark, like the Shadow Queen’s theme and battle music, to climactically uplifting.

13 – The Void: Unlike the original PM64, the game doesn’t have the luxury of having the loss of Peach’s Castle serve as a literal void. The game surely employs the boss-battle- in-a-big-room strategy (one of the plot points in Chapter 3 is to “never go to the Glitz Pit when no one is around,” reinforcing this notion). The Void is more thematic in terms of darkness.

I think the best use of The Void in this game is the entryway to the Thousand-Year Door itself. The room is spacious, larger than any other you’ve encountered so far, and it feels intimidating. Then, when the Door finally opens before Chapter 8, a giant void opens that you have to walk through. This scene connects everything: The Void = The Thousand-Year Door = The title of the game = darkness that you have to enter in order to save Peach = your challenge, mechanically, to fight on the side of light = the theme.

14 – Inner Calm: Just like the original, there is emergent complexity in the gameplay as you unlock new party members, hammers/boots, badges, paper abilities, etc., which gives you more stuff to do. But, unlike the original, there is inherent narrative emergent complexity, which builds as well.

You don’t learn that the Door houses a thousand-year-old demon until well around the 1/3 point of the game. You don’t learn about the X-Nauts as a race until Chapter 2. You don’t learn about Grodus having nefarious plans for Peach until the 2/3 point of the game, after Chapter 6.

Additionally, there is a Rogueport denizen, Grifty, at the top of a roof on the eastern side of town that, for a price, will tell you information about the backstory of Rogueport, the Thousand-Year Door, the Crystal Stars, and the Shadow Queen. As the game progresses, more and more tidbits become available to learn about. This is a nice bonus feature for the sake of emergent narrative complexity.

15 – Not-Separateness: It can be argued that the physical world of TTYD is more separate and bounded than in PM64, as each chapter you get to is from either a pipe or a far-away piece of transportation like a blimp, train, or ship (as opposed to just walking to it). But thematically, everything is more interconnected by the themes. Again, mechanically, this is also reinforced in Chapter 4 when your party is stolen from you, and you then lose some of your abilities and your aesthetic body. Darkness winning = you losing things.

So, that is TTYD.

Admittedly, the overworld is stronger in original PM (related to carrying letters and more sidequests littered across the world, with more directions to move in, less backtracking, and a wider gameplay space). Peach also has more to do and Bowser is much more threatening in PM64. But the narrative is stronger in TTYD.

Basically, TTYD takes Mario characters + Mario structure + RPG Mario mechanics and builds on it.

I posit, and remain steadfast in my belief to this day, that TTYD is the greatest Mario story ever told, which builds off of its IP’s rich history, combines it with iconic archetypes of light vs. dark, and reinforces all of it through its mechanics and characters.

Challengers to Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door

What about other Mario games? I just recently played the most recent Mario title, Super Mario Odyssey, for the first time, and its narrative is not nearly as strong as TTYD’s, but other Mario games and other Mario RPGs have come close. Let’s go through a few of them:

NOTE: For this section, I am not using A Nature of Order as direct criteria. I am touching more on cohesion of themes, characterizations, plots, and depth in the following games. These reviews, for this post’s sake, will be brief. For an expanded exploration on these additional Mario games, please read here.

Super Paper Mario (Nintendo Wii, 2007): This is the most obvious counter-example. Because, on a pure story and plot basis, the main narrative is arguably more powerful than TTYD’s.

The story is about a LITERAL VOID (called the Void) that is opened up by the game’s main villain, Count Bleck, that threatens to destroy all universes and you have to collect all of the Pure Hearts in order to counter the Chaos Heart, which is powering the Void, and thus save all worlds (playing as Mario, Peach, Bowser, and Luigi). At one point we actually see a world destroyed by the Void and reduced to nothingness, which might be the darkest moment of the entire Mario canon.

You eventually find out that Count Bleck is a broken soul, who turned to hate when his girlfriend Timpani was erased from his world; and that your Pixl partner Tippi is actually Timpani in a different form.

Finally reunited at the end, Count Bleck (whose real name is Blumiere) and his true love unite, destroy the Void, and save the universe. They presumably die, but the ending shot of the game is of the two of them off somewhere in the distance, suggesting that maybe they got their happy-ever-after after all.

It is a beautiful story. It employs the tried-and-true Mario structure of chapters and collecting valuable objects, and employs light vs. dark again to great effect.

And the mechanics betray it.

The game tried to be a platformer and an RPG at the same time, and it just… honestly doesn’t work.

Some of the niche moments of switching from 2D to 3D to unlock puzzles is mildly entertaining, but the platformer aspect dilutes a lot of narrative momentum. Especially when a handful of later boss fights, even the final boss, end up being beaten very easily after a lot of buildup.

The Paper Mario series often gets flack for a somewhat minimal difficulty curve, but at least some of the later chapters in the earlier games take strategy and time.

So, yeah – Super has a great main plot, great villain in Count Bleck, great twists, and great arcs for characters such as Luigi or Dimentio. But the rest of the game fails to support these elements.

NOTE: I have since replayed Super Paper Mario and, upon further review, felt that it was worthy of a deeper analysis, so I have constructed two new posts reviewing the game. The first post applies A Nature of Order to SPM, exploring its thematic depth and complications. The second post explores SPM as the culminating entry of the Paper Mario trilogy, and serves as a retrospective on the series as a whole.

Mario + Luigi Series (GBA/DS/3DS, 2003-15): I enjoy this series very much. I am combining them here into one category to save some space, and also because these games, especially the first three, are similarly structured, with Mario and Luigi partnering together to explore an open world.

Mario has more of a personality (that of a somewhat annoyed, frustrated individual that keeps having to be the one to save everything and everyone, including his brother) and Luigi’s rich personality is always a wonderful addition to the narrative.

The main plots of these games are very intricate. You often see the effects of the villains’ plans on the world, and the games in this series mix up the narrative arguably even more than the Paper Mario games do. Although each game typically involves the collection of star-shaped MacGuffins, this collection process is not chapter-based, and you often get sent around an open world on more nuanced missions.

However, while this makes these games interesting from a plot perspective, it actually makes them feel less like “Mario” games. Remember, the original structure going all the way back to the original platformers employs direct chapter boundaries. Whereas the Paper Mario series expands creatively within this structure (and also employs Strong Center “hubs” like the 3D Mario games do), the Mario + Luigi series more or less breaks this structure. Characters that are somewhat ridiculous further this notion.

Again, I enjoy these games very much, mainly because Mario & Luigi probably have the MOST personality in them compared to any of the other games. And the plots are intricate enough to satiate. But somehow the world around our protagonists and plots feel less developed, and, well, less “Mario.”

Super Mario RPG (SNES, 1996): Regardless of its successes and flaws, I give this game a lot of credit. It was Nintendo’s first Mario RPG, and its success directly led to the Paper Mario series as well as the Mario + Luigi series. Without this game, the rest would not be possible, and the game is extremely ambitious to boot.

The plot, involving you needing to collect seven star pieces to restore the Star Road, which was destroyed when a sentient sword crashed into Bowser’s Keep, is very intricate and emergently complex. You also get to play as Bowser and Peach, as well as two original characters – Mallow and Geno.

You can see the aspects that the rest of the Mario RPGs draw on – Mallow and Geno very much represent the “original characters” from the story world who get drawn into Mario’s party due to their own missions and then help in saving the world, a precursor to the Paper Mario party members.

Also, SMRPG has the overarching plot of collecting seven star-shaped MacGuffins in order to restore a magical artifact and prevent chaos, which every Paper Mario employs in some form afterward.

But overall, there are a lot of plots in SMRPG that need to be resolved (from the mission to restore the Star Road, to stopping Smithy, to saving Bowser’s Keep, to finding Mallow’s parents, etc.). And there is a lot of chaos to how some of them are drawn out. These plots are less unified compared to the Paper Marios.

Almost all of the elements that Nintendo would deepen in later games are present in SMRPG, and the game feels as such – the game has so much in it, it is bursting at the seams. The gameplay and battle system are fantastic (which Nintendo would expand on with the Mario + Luigi games), arguably the most challenging of the series right from the start. The A plot is complex with a handful of nice subversions, but the characters are not as deep as later installments. SMRPG can sometimes be all over the place.

And it’s hard to fault it. We’re talking about a game that precedes all other Mario RPGs, and it tried a lot of ambitious, nuanced, challenging gameplay and story elements that still hold up all these years later. In a way, SMRPG had to run so PM64 could walk, so that then TTYD could jog in balance.

Super Mario Galaxy (Nintendo Wii, 2007): For me, this game comes to closest, narratively speaking, to the thematic depth of the original two Paper Marios. Firstly, it employs a mechanic that, at its time, was wholly original: planet-hopping and using gravity in nifty ways.

Bowser, like in the original Paper Mario, feels menacing. Like in Paper Mario, he lifts Peach’s Castle from the sky and disappears into space, leaving (you guessed it) a thematic void that you have to go and save.

And the theme – that of the cosmos themselves being in danger – is reinforced by Rosalina. If Count Bleck is the richest Mario villain put to the screen, Rosalina is maybe the richest supporting Mario character put to screen, and especially the richest female supporting character.

In slow, emergent side-readings, you learn how Rosalina became connected to the cosmos and the Lumas, for whom she now cares for. She comes to represent a “Mother of all the Cosmos” type of character – basically, she cares for space itself. And, from the very beginning, she has been kind to you in your own journey.

So, yes, you need to rescue Peach because you need to rescue Peach. And you need to save the world because, well, it’s a Mario game. But additionally, you’re also doing it for Rosalina. The story becomes as much about repaying her kindness with your own heroism.

Also, I’ll be honest: it is refreshing to see a female Mario character used in an elegant way – a woman who represents knowledge, love, wisdom, and knowledge without a HINT of romantic overtones. She represents love on a grander, much more powerful level that in some ways is hard to put to words. But you feel it when you play the game.

The story in Galaxy is not back-and-forth like TTYD is, but, like the original Paper Mario, it employs a simple story structure at the beginning that is reinforced by original mechanics and powerful music. And the game has one supporting character that transcends everything else.

Super Mario Odyssey (Nintendo Switch, 2017): The last game on this list I am including due to it being the most recent mainstream Mario game. Upon playing it, the game reminded me of PM64 at first. Like PM64, Odyssey has your favourite “Mario” worlds but with some twists thrown in. A grass land, desert land, water land, forest land, and ice land are all present, but then there is a food land… and a metropolitan land too!

Also, like the Paper Marios, each chapter has a world or town that has been overrun with Bowser’s minions and you need to defeat these bad guys to restore order to the town. The towns don’t necessarily build on each other, but tell interesting mini-stories in and of themselves.

But unlike PM64, which focuses a lot of its attention on its worldbuilt characters and repairing what Bowser broke, Odyssey, by contrast, is a chase story – a story in which you are trying to prevent the horrible event from occurring.

Overall, the worlds feel less significant to the main plot. Again, Odyssey is a chase story at heart. Because the fear of being too far behind Bowser is too great, it’s like “okay, that’s great, NPCs, but I have to chase Bowser.”

The Metro Kingdom is an exception because you feel connected to wanting to help Mayor Pauline in particular, and Odyssey would have worked well if the worlds that follow the Metro Kingdom had NPCs as strong as her, but they do not. After the Metro Kingdom, the NPCs are fairly nameless, just like they were before the Metro Kingdom. However, in the first half pre-Metro Kingdom, you are hooked by the tension of the chase. By the second half, this momentum feels stalled.

If the back half of the narrative had given you more named NPCs to feel pain with as a result of Bowser’s actions, then the first half would be the chase movie that you lose, and then the second half, now that you’re well behind Bowser, would be all about feeling the effects of his actions on the worlds.

But again, Odyssey is not focused on a worldbuilt theme like PM64 is. So, when the momentum of the chase stalls, there is less of a narrative to lean on.

Now, the gameplay is excellent, if not perfect. Odyssey might be the most mechanically sound game I’ve ever played, and the nuances of the different enemies you play as are fantastic. The worlds are vibrant, the pace is very brisk, and, even with these narrative criticisms, it was a very rewarding gameplay experience.

But story-wise, it is not in the same ballpark as the other games mentioned here.

Lastly, in mentioning the last two elephants in the room, Sticker Star and Color Splash, I’m not even going to talk that much about them, because enough people have. Nintendo sacrificed its story completely in these games in favor of gimmicks that actually harm the traditional mechanics. I still retain hope that a Paper Mario 3 will eventually come into the world that actually honors its predecessors, though with the direction Nintendo is moving in (favoring more “fun” party games or reboots with twists on them, instead of more mature content), I also have my doubts that this will ever come to pass. Until then, we always have TTYD.

Flaws in My Perfect Narrative

Returning back to TTYD after these detours to other Mario games, there is one more question: is TTYD perfect? And the answer is, well, no. Even my favorite game has flaws in its narrative, most noticeably in Mario as a protagonist.

If TTYD is the best a Mario story gets, what are its flaws?

Well, firstly, I pointed that the story’s denouement tries to undo a lot of the story’s darker moments in favor of a “happy” ending. Vivian returns to be with her sisters who are magically nice to her now, which honestly is not a good message to be sending out to people who might identify with Vivian. Grodus and Crump somehow survive being disintegrated and launched into space, respectively, diluting the power of their presumed deaths. And TEC, who has a sad, believable on-screen death, is revealed to still be functional without much explanation.

I forgive these last moments because they are in the denouement and don’t affect the larger story or the mechanics, but I wish the story had maintained its darker yet empathetic overtones 100% to the end.

But even more so, Mario still doesn’t change. There is no Hero’s Journey. The people who go through the journeys are the party members, or certain NPCs like TEC. Thinking about both SPM and Galaxy, it is Count Bleck and Rosalina, respectively, that have the character arcs that ground the narrative.

Mario can be anyone, which allows you to feel like you are him, but he himself has no real issues or anything to overcome. There is no wound that creates a lie that Mario believes, which then must be overcome in order for him to achieve peace.

There are tons of iconic archetypes Nintendo could draw on if it wanted to give Mario, and, by extension, you, a true journey. There are different kinds of heroes, from Classic to Iconic and so on.

Compared to Luigi, who at least changes somewhat in his games like Luigi’s Mansion (i.e. growing some courage), Mario doesn’t.

As stated earlier, TTYD tries at least a bit to draw attention to this. In TTYD, the party members are down-and-out characters that we all can relate to. These partners (and other characters like King K) highlight different aspects of Mario’s personality that he can’t express (like certain aspects of real love or of a “protector” type).

Yet, this is also arguably a problem. Mario is defined A LOT by love interests (heck, the core plotline of the entire series is rescuing Peach, even though in some games she gets more of a sneaky and developed personality), and ALL of the four women in TTYD have romantic overtones with Mario, which is a bit of a limited perspective.

In PM64, the female partners are less pseudo-love interests than in TTYD, yet they’re also less developed, and yet they are STILL often defined by love interests. Bombette has an ongoing not-relationship with fellow Bob-omb Bruce, and Lady Bow has her trusty Boo butler, Bootler, who’ll do anything for her.

Anyway, the Mario series can learn from having female characters like Rosalina who are not defined by romance and have their own personalities and feminine strength independent of romance.

These are issues rooted in the Mario structure, so they’re not going to change overnight. There has yet to be a Mario game that employs all of these attributes to perfection. TTYD may have the series’ best beat-by-beat interconnected thematic narrative, but Super Paper Mario has the series’ best villain. Galaxy has the series’ best female character. The Mario + Luigi series showcases Mario and Luigi at their most personable. Maybe one day, Nintendo will make a new game (perhaps a true Paper Mario 3, perhaps not) that gets everything right.

Is TTYD perfect? Naw, it isn’t. But right now and for the foreseeable future, when it comes to Mario, it’s the best we got. I for one have replayed it at least six times, and will continue to do so. Thanks for reading, and, if you have, thanks for playing!

[1] Jesse Schell, The Nature of Order in Game Narrative, GDC 2018, https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1025006/The-Nature-of-Order-in

The Rest of My Mario Narrative Series

Challengers to Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (Expanded)

Deep Analysis of Super Paper Mario: A Nature of Order Applied to a Complicated Narrative

Paper Mario: The Origami King – Give it a Chance to Make an Impact

Additional Analysis

Paper Mario Design Analysis and Retrospective – Super, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6L3d9GLzzI

The 5 Best Aspects of Paper Mario 64 – Snoman Gaming, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KHolbrhpKI&t=3s

Paper Mario | Red Review – The Red Guy, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqwg2J7kzN8

Good Game Design – What Makes a Great Sequel ? (Paper Mario TTYD) – Snoman Gaming, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPvEGVL0ouI

Paper Mario The Thousand Year Door | Red Review – The Red Guy, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-VkfRPFoj4Y&t=3263s

Core Systems Analysis of Paper Mario TTYD – Tyler Grendel, Gamasutra, https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/TylerGrendel/20200506/362403/Core_Systems_Analysis_of_Paper_Mario_TTYD.php

The Super Mario Franchise Offers Up a JRPG for the Ages with Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door – Collin Henderson, https://25yearslatersite.com/2020/03/18/the-super-mario-franchise-offers-up-a-jrpg-for-the-ages-with-paper-mario-the-thousand-year-door/