For my post on Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (TTYD), I used Christopher Alexander’s A Nature of Order as the lens by which to analyze both that game, its predecessor Paper Mario (PM64), and the basic Mario structure. Of all the games that I then touched on as challengers to TTYD, one game stood out to me as worthy of deeper analysis, especially after playing it again recently. Super Paper Mario (SPM), the sequel to TTYD, is known as a game was a fantastic story, but also a game that has clear flaws. As the immediate successor to TTYD, it is only fair that I apply the same lens to Super Paper Mario.

Note: This post concerns an advanced, design-based analysis of SPM by itself, but this analysis is part of a greater discussion on Super Paper Mario within the context of Paper Mario as a series. View my analysis of SPM in terms of the Paper Mario series as a whole here.

For the uninitiated, these patterns that Christopher Alexander explores in A Nature of Order can be described as such, in which he posits that there are inherent patterns in architectures, games, life, that, when employed and noticed, create a pleasurable feeling that things are balanced, comfortable, all right [1]:

- Levels of Scale: We are constantly interacting with things small, medium, and big, and changes in these scales can be seen and felt.

- Strong Centers: We are interested in things, like the solar system or atoms, that are centered.

- Boundaries: Boundaries create centers, and there are also physical and thematic boundaries that need to be crossed in order for change to occur.

- Alternating Repetition: We like going back and forth, like falling/rising tension flow in a story, or checkerboard patterns. They are pleasing.

- Positive Space: There is an interplay between positive and negative space. Sometimes negative space can enhance positive space.

- Good Shape: We like shapes that are not trying to be pretty but, through their inherent purposes, make pleasing shapes, like sails catching the wind.

- Local Symmetries: Our brains are programmed to spot tiny symmetries (i.e. in our bodies, between characters in a story) that feel connected, even if, globally, they are not.

- Deep Interlock: We like the feeling that things are interconnected, that things which happened ages ago, that felt meaningless at the time, have some significance. Characters, stories, mechanics, themes, must feel connected or the feeling starts to fall apart.

- Contrast: We can perceive two things brought together in unexpected ways, or one thing (like comedy) enhancing another thing (like tragedy).

- Graded Variation: This regards things changing overtime; things we can’t spot instantaneously but when we look back at them, we realize the change that happened between now and then.

- Roughness: We don’t want characters and things that are 100% smooth, because imperfect things feel human, real, and natural in their messiness.

- Echoes: One thing echoes another, like game mechanics or characters echoing the central theme of a story.

- The Void: Oftentimes the most important things are in empty spaces.

- Inner Calm: We are not given all the information at once, so that emergent complexities can come out through natural tension.

- Not-Separateness: We like the feeling that pieces, even if they are physically separate, are not, and that if you take one piece away, the other suffers. The world is connected.

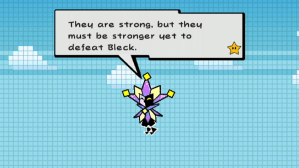

A brief summary on Super Paper Mario‘s story: Mario and his immediate companions travel through dimensions to collect the eight Pure Hearts to counteract the Chaos Heart, and thus stop the villain, Count Bleck, from erasing all worlds using the Void. The Void itself is being powered by the Chaos Heart, as is foretold in the Dark Prognosticus. As the game states in its opening cutscene: “This is a love story.” Outside of some flaws in its mechanics, most of its narrative elements support this story. Further analysis reveals more about how the game’s narrative complexity reveals its core themes of: hidden depth, true love saving the world, and balance between Light and Darkness.

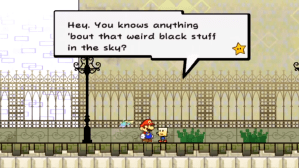

1 – Levels of Scale: From the beginning, we can see how SPM is inconsistent from its predecessors. The small-scaled battle screen is gone, as is the larger overworld map to look at (although you can look at pictures of the worlds you visit, and, since the worlds are not connected away, can at least see a larger structure of your journey). And yes, the 2D can switch to 3D, but this feels like a flip between two POVs on the same level of scale, rather than different levels of scale.

However, SPM does have chapters (medium levels of scale) made up of sections (small levels of scale), which all together make up the greater narrative (large levels of scale).

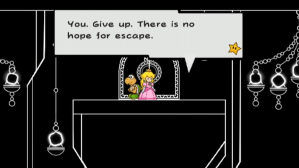

2 – Strong Centers: Like its predecessors, SPM has two physical Strong Centers: Flipside/Flopside, and Count Bleck’s dark realm… but also one key addition. The opening pre-credits screen has you viewing the Dark Prognosticus set against a black screen, so you are set up be thinking about these dark spaces before the game even starts.

The game teases past central areas like Mario’s House and Bowser’s Castle before settling in on Flipside. Flipside as a town feels like less of Strong Center than the previous two games, as the town itself isn’t necessarily rooted in lore or feeling the effects of the prologue in a strong manner. It feels like you are passing through it.

However, Flipside is important because it is where Merlon resides, the one of the Ancients parsing through the Light Prognosticus. Flipside is important because it is the representation of that light – the worlds you are trying to save. In the same way Count Bleck’s realm, which you visit in between each chapters in cutscenes, represents the darkness surrounding the Dark Prognosticus.

But more than that – you realize that Flipside represents Tippi, who is closest with Merlon and who calls Flipside home, at least now. In the same way Bleck’s realm is representative of Count Bleck. It is no accident that, in addition to visiting Bleck’s realm and Flipside in between each chapter, you get a text-backstory scene from Blumiere and Timpani.

The game is telling us that its true Strong Center is Bleck and Tippi (a.k.a. Blumiere and Timpani) together. And at the start of the game, they are split into two different centers, one of light and one of darkness. Compared to the end of the game, that closes with the two of them walking away together, these centers unified as one.

In this sense, SPM has the strongest Strong Center of the trilogy.

3 – Boundaries: The game employs boundaries more similarly to earlier Mario games. Each world can be accessed by walking through one of the multi-colored doors on the Flipside Tower (with the last door accessible on the Flopside Tower). Throughout the game, you are unlocking new boundaries/thresholds to different worlds to find more Pure Hearts. There is less of a main boundary in this game (compared to boundary between you and Peach’s Castle in PM64, and the recurring boundary of the Thousand-Year Door itself that reinforces its theme in TTYD), and more several smaller ones.

The last door, which appears on the Flopside Tower and leads to Castle Bleck, is treated as significant, but because the boundary hasn’t been reinforced the same way that the Thousand-Year Door was, it doesn’t feel as significant in a physical sense. It does so though in a thematic sense because we’re finally reaching Castle Bleck which we’ve seen in the interlude and because of the intense stakes.

This is one of the categories that indeed makes the game feel like a Mario game, with the chapters and the boundaries to reach them, but also makes the game feel more trimmed down compared to its predecessors, especially in the beginning before you realize the depth of the Strong Center.

4 – Alternating Repetition: It says something that, on a macro level, the game employs as strong of an Alternating Repetition as there is, as we come to realize the pattern of completing a world and then Pure Heart, then followed by a small scene taking place at Count Bleck’s domain, and then followed by a Blumiere-Timpani cutscene, and then followed by a reprieve at Flipside. So there is World / Castle Bleck / Blumiere-Timpani / Flipside / World. We can see from the beginning that the game is hiding its Strong Center with this repetitive sequence.

Also, I think that it is clever that, in terms of these Count Bleck cutscenes, they first play out as interludes featuring Peach and then Luigi, making you think that the game is allowing you to play as other characters in the same way as PM64 and TTYD. But no. Peach and Luigi feature in the first two Castle Bleck cutaways, but the setting itself (and by association Count Bleck and those connected to him) is more important than the familiar characters.

However, on a micro level, SPM is weaker compared to its predecessors.

I mentioned in both PM64 and TTYD that each chapter employs an overworld, a dungeon, and a hub, and then over time plays around with the order of these areas. Unfortunately, in SPM, there are no great hub spaces, or no great spaces that feel like hub spaces, beyond Flipside – areas where there are no enemies and you spend time meeting characters, resting, buying items, and finding clues. There are chapters where there are some spaces where you can do so, but these areas don’t take up enough space to feel like true hubs. They are not sprawling that much with NPCs. The item shops in particular are often small reprieves in the middle of overworlds filled with enemies. Let’s take a look:

-

-

- Chapter 1: Lineland Road ⇒ Yold Town (mini-hub) ⇒ Yold Desert ⇒ Yold Ruins (dungeon)

- Chapter 2: Gloam Valley ⇒ Merlee’s Mansion (mini-hub/dungeon)

- Chapter 3: The Bitlands ⇒ The Tile Pool ⇒ The Dotwood Tree ⇒ Fort Francis (dungeon)

- Chapter 4: Outer Space ⇒ Planet Blobule (mini-hub) ⇒ Outer Limits ⇒ Whoa Zone (dungeon)

- Chapter 5: Downtown of Crag (mini-hub) ⇒ Gap of Crag ⇒ Floro Caverns (dungeon)

- Chapter 6: Sammer’s Kingdom ⇒ World of Nothing

- Chapter 7: The Underwhere (mini-hub) ⇒ Underwhere Road ⇒ Overthere Stair ⇒ The Overthere (mini-hub/dungeon)

- Chapter 8: Castle Bleck (dungeon)

-

Although Chapter 1 almost seems like a direct symmetry to the earlier games, employing an overworld, a mini-hub, and then a dungeon, this pattern for the most part then goes away. Merlee’s Mansion has some NPCs to speak to, but mostly serves as Mimi’s extensive dungeon filled with traps. Chapters 3 and 4 more or less are adventure chapters moving from point A to point B. The later chapters employ a sense of fantastic Contrast (see below) in their locations and themes, but there is less a pattern to the chapter design. You can expect a four-part chapter, and you know that there is a dungeon with a boss at the end, but outside of that, you do not know what to expect.

Maybe this is the point. The “villages”/mini-hubs all are very much close to darker/combat regions, which feels like, once you are in a Chapter, there is no real space to catch a breather. Then again, not all dungeons feel like true dungeons either. Although the Floro Caverns is the final area in Chapter 5, it is also just where the Floro Sapiens live. And the Overthere has been taken over by Bonechill’s minions, but is actually meant to be a place of peace. Blurring that line between what is dark and what is “good.”

If anything, the only “pattern” that gets exploited is in Chapters 6 and 7, when at this point you have gotten used to the four-part structure of the Chapters. But Chapter 6 is cut short when the world is destroyed, so this direct feeling of “offness” to this pattern mirrors the gut-punch of the destroyed world. And then Chapter 7 begins with you having to escape the Underwhere rather than with a traditional beginning, leaving you feeling scattered and needing to pick up the pieces. Then Chapter 7 is about picking up those pieces (a.k.a. restoring your party) before Chapter 8 introduces the danger of losing them.

The key here is that, for the most part, the world-building patterns employed in the earlier games are gone, outside of the macro level, and there is very little in terms of knowing what to expect next. Once you realize it, it is not inherently a bad thing, as it means other, larger-scale thematic elements can take focus. But early on, before that realization takes place, it’s a bit scattershot as you’re not sure what the focus is.

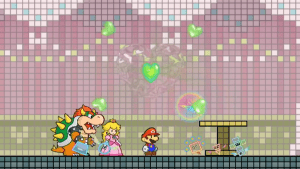

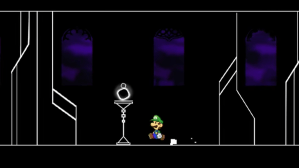

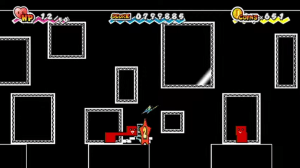

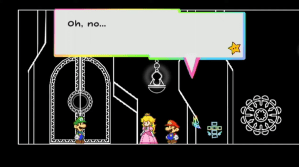

5 – Positive Space: This is employed very well, especially in the final level when everything is dark and black. The bright reds and greens and pinks and yellows of our heroes stand out so much compared to this setting, it very much feels like we come from a different world, and we do. We are the people of light here in this completely black setting here to save the world. This is also true when we see our heroes set against the World of Nothing.

Also, it’s worth a thought that there is no Positive Space in the Blumiere/Timpani interludes, just text, perhaps saying that this love story only exists as a memory, not a reality, but it still exists, and the game is all about bringing it back to the Positive Space.

6 – Good Shape: There are a lot of interesting shapes in Super Paper Mario, as the game employs a lot of wonky aesthetics that make the world feel blocky and paper-y, but in a very creative way, like some of the enemies that are just composed of a handful of multi-colored lines. And yes, it can be immediately interesting to find yourself fighting with an enemy that is basically a stick figure, which wouldn’t be threatening except for the fact that it is attacking you. But not much beyond that.

This is also true of the Pixls as well, as the shape of each Pixl is a clever indication of the type of ability that they provide. Thoreau, which allows you to throw things, is a hand. Thudley, which allows you to ground pound, is a weight. It leaves you wondering about how this connection between aesthetic and ability works, especially for the more creatively drawn Pixls like Dottie or Dashell.

But none more so than Tippi. At first glance, she appears to be the most basic of all of the characters, including the other Pixls. She has no eyes, is just four triangles drawn together and animated to move like a butterfly. But this lack of standout features allows her deeper personality to grow and grow and grow.

It allows us to, overtime, slowly project more and more of her backstory onto how we view her. And this is reinforced by the game because there are periods of time when her backstory becomes too heavy for her and she needs to rest and be revitalized. And we begin to realize how much history, and pain, and love are all present in this tiny, fragile creature.

If there is any example of a good shape harboring hidden depth, Tippi is a better example than pretty much anything or anyone else in the entire series.

Tippi isn’t trying to be a butterfly, as the shape indicates. But as her personality becomes deeper, we realize that she is in spirit.

Additionally, as you open more worlds, you add more different-colored doors to the Flipside Tower, and overtime, it creates this beautiful, rainbow-esque palette that culminates in a symmetrically balanced shape as well. So, your progress in the game is reinforced by the creation of this beautiful shape.

7 – Local Symmetries: Like the first two games, there are plenty of local symmetries between some enemies. Not as much, as there is little symmetry between a creature (like a Koopa) being both your friend and your enemy in the same game. But, just like the first two games, enemies you meet in the earlier chapters then are reestablished as dark echoes in later chapters, like Wracktail, a more difficult mirror of the Chapter 1 boss Fracktail, appearing in the Flipside Pit of 100 Trials; or the uber-strong Mega Muth appearing in the final chapter of the game after the original, prehistoric Muth was introduced in Chapter 5.

The biggest world-related symmetry is between Flipside and Flopside, the town that exists behind a 3D mirror, and thus acts as a mirror image of Flipside, both in tone and space. Denizens you meet on Flipside are present as complete mirror images in Flopside, and these denizens speak the opposite of what their Flipside denizens speak about. In Flipside, there is a writer hanging out struggling to make ends meet just before the Flopside entrance. On the Flopside side of this area, there is a similar writer character, only this one has intense confidence and is very successful.

These towns are not presented as rivals, or as one as “good” or one as “evil.” These towns are two sides of the same coin: life. So, the game is telling us that, even if there are people literally saying and doing opposite things on the opposite side of town, we are all on the same side. Outside of the main storyline, this might be the most impressive aspect about SPM’s world-building.

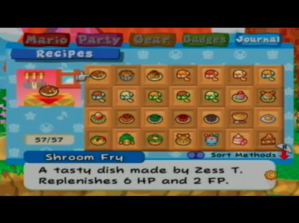

In addition to visual symmetries between the recipes you cook and the previously mentioned symmetry that becomes present on the Flipside Tower, the biggest in-game symmetries are those present in the final chapter.

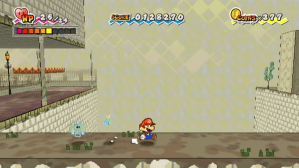

With each major fight at the end of each Chapter 8 section (i.e. Bowser-O’Chunks, Peach-Mimi, Luigi-Dimentio), the game invites you to think more about symmetries (and contrasts) between their character personalities as well. Bowser and O’Chunks are both tough guys with hidden depth. Peach and Mimi can both be a bit spoiled, but go about their lives in different ways. Luigi, unfortunately, can be as egoistic as Dimentio if he wants to be, but for the most part he doesn’t, and that is what makes him a good guy different from Dimentio… but also susceptible to him.

The final battle then teases a furthered pattern of potential symmetrical comparison between Mario and Count Bleck, but in truth the real symmetrical comparison is the aforementioned one between Bleck and Tippi.

8 – Deep Interlock: Yes, especially so on a character/thematic level, but less so on a world level. I mentioned in the TTYD post that TTYD strikes a fairly perfect balance of mining out emergent, interlocked mysteries as the game progresses, while also including self-contained in-chapter mysteries, with things becoming more important overtime as the chapter progresses (which prior to TTYD was what PM64 did).

SPM has the larger scale mysteries down sublimely, especially given their connections to the themes. As part of this section, I will also touch on SPM’s effort to make Deep Interlock across its Mario canon and especially the Paper Mario series. Even though the in-chapter mysteries were somewhat lacking, especially at first. Let’s see:

-

-

- Prologue: Bowser and Peach (two people of great Contrast who will later end up on the same team) are forced into marriage. We are introduced to the wedding chapel locale (which will return in the game’s climax), Luigi as a character that wants to help but is unsuccessful, as well as the initial character personalities of Bleck, who wants worlds to end, as well as Nastasia, his devoted servant. Later so, Tippi and Merlon are introduced when Mario is brought to Flipside.

- In terms of the larger series expectations, this prologue gives you the expected (Peach is kidnapped and Mario has to start from scratch in a faraway place), but also the unexpected:

- The prophecy is already set in motion by the time the prologue ends (as opposed to TTYD), Bowser is portrayed as a major player, but not the Big Bad, and Luigi is immediately telegraphed as important, unlike previous games when he exists in the background.

- Chapter 1: There is very little mystery to this chapter beyond getting to the end, defeating Fracktail, and obtaining the Pure Heart from the Ancients. Bestovius and Yold Town exist here but do not reappear again. However, here is your first encounter with O’Chunks and Dimentio. O’Chunks comes off as a tough guy who isn’t that tough. Dimentio, who brainwashes Fracktail into fighting you, comes off as a guy who has fun causing mischief.

- What Chapter 1 does well is powering through the expected introductory Mario worlds (grass land and desert land) in one chapter, complete with an entry-world boss in the form of a dragon (like Hooktail was), existing as “the chapter of the expected” before expectations start being subverted.

- What Chapter 1 does well is powering through the expected introductory Mario worlds (grass land and desert land) in one chapter, complete with an entry-world boss in the form of a dragon (like Hooktail was), existing as “the chapter of the expected” before expectations start being subverted.

- Chapter 2: Although there is a mini-mystery of uncovering the machinations behind the forced labor workers in Merlee’s Mansion, this doesn’t get much deeper than finding a cheat to pay off Mimi’s rubee depth. The chapter more or less introduces Mimi as a character that likes to set traps for you and play with the people she has captured, and who can also turn into a twisted spider.

- Chapter 2 is also the first chapter you can play with Peach, so it also exists as an introduction to the “new normal” of SPM, where saving Peach is not the mission, and where there are bigger stakes at play.

- Chapter 2 also is a “light” return to Paper Mario series expectations. Whereas Chapter 1 feels very much like a level out of the older Mario games, Chapter 2, with a slightly deeper mystery and at least some NPCs to speak to in order to help solve it, feels closer in tone to the first two Paper Mario games. It even touches on some higher-level themes of forced labor. It not on the exact same level as the earlier games in terms of worldbuilding, but it’s at least close.

- Chapter 3: There is the bonus of getting Bowser to join the party, and though this does feel like a payoff to wondering where he was, it is less an in-chapter mystery (you hear some NPCs talking about a monster at the end of Chapter 3-1, and it turns out to be Bowser, but that is about it). It is more another subversion in telling you that Bowser is firmly not the villain in this story. Afterward, the plot is mainly about getting to Fort Francis to get Tippi back. Francis is a very unique character, so even though the world around this chapter isn’t especially deep, at least Francis brings some immediate wacky flavor to the game. Along the way, some moments do stand out:

- The first fight with Dimentio comes off as very interesting. Whereas O’Chunks genuinely feels like he is not tough enough to beat you, Dimentio more or less states that he is fighting you to size you up and see if you can take on Count Bleck. This is the first instance of seeing Dimentio as a potential traitor.

- In addition, you feel the brief loss of Tippi (mechanically speaking, see below) and, after you save her, the burgeoning affection she feels for you reveals the next Pure Heart. This twist that Tippi’s affection is more important than just finding a Pure Heart hidden somewhere suggests that the Pure Hearts are more than just MacGuffins, they can be representative of genuine love and affection. Plus, this reveal illustrates that Tippi is far more important than it first seemed. Lastly, the affection that Tippi feels here is contrasted with the forced affection that Francis wants from Peach. So the game has shown us a “love” that is twisted before showing us a love that is genuine, using the thematic Echo of both the past games (Peach) and the current game (Tippi). In a way, the game transfers its thematic symbolism from Peach to Tippi in this scene.

- Again, we see the more macro-level mysteries and themes having some nice foreshadowing moments, but with the in-chapter story beats feeling straightforward.

- The first fight with Dimentio comes off as very interesting. Whereas O’Chunks genuinely feels like he is not tough enough to beat you, Dimentio more or less states that he is fighting you to size you up and see if you can take on Count Bleck. This is the first instance of seeing Dimentio as a potential traitor.

- Chapter 4: Like Chapters 1 and 3 where it was an adventure from point A to point B, the chapter plays out with you more or less following Squirps to get to Point B.

- The reveal that Squirps is actually the prince of a space kingdom is a… reveal, but because Squirps’s identity isn’t treated as a mystery that is that important makes the reveal feel a little basic. What is more interesting is that Squirps’s family hid the Pure Heart in the Whoa Zone 1,500 years ago, and that Squirps was awakened from hibernation to bring the heroes to it. Thus, this introduces the idea of people around the worlds (not just Merlon’s people) existing as protectors of the Pure Hearts. While this reveal would have been stronger if we had seen more bits of Squirps’s long-lost kingdom along the journey, the reveal itself does carry interesting macro-level themes.

- More important is the first arrival of Mr. L, which answers the question of “what happened to Luigi” and illustrates the capability of brainwashing in this universe.

- Overall, Chapter 4 is very unique, “out there” chapter that leaves few comparisons to the original games, but Mr. L further showcases the elevation of Luigi in this game’s narrative, and Squirps, while not harboring as much of an in-chapter mystery as some would have liked, does carry more thematic weight than we initially expected.

- Chapter 5: Here we go. Now, in-chapter events start happening that create some interlocked tension.

- The chapter begins with a handful of Cragnons being kidnapped by Floro-Sapiens, and, unlike the previous chapters in which you are told where you need to go and then you just need to get there, here you spend a lot of time following these Floro-Sapiens, so a buildup is created of wondering where the Cragnons are being taken, what the Floro-Sapiens are doing with them, and where they are leading you.

- You fight O’Chunks again, which doesn’t reveal a whole lot more about him, but it becomes very important when you run into Dimentio again. In the Floro Caverns, you discover that Floro-Sapiens are brainwashing the Cragnons by planting Floro Sprouts in their heads. Dimentio appears with O’Chunks, and, after some playful barbs, snaps his fingers and a Floro Sprout appears on O’Chunks. Dimentio then sets him on you. He is still beatable, but it is important to notice that Dimentio is now experimenting with brainwashing techniques, as this is what he will do to Luigi in the game’s climax. What’s more, the Floro Sprout that O’Chunks drops after you beat him turns into the Important Thing you need to use to get past the Floro-Sapien scanning mechanism to reach their leader, King Croacus IV.

- So, here we have a moment that not only answers an in-chapter mystery (the Floro-Sapiens are using Floro Sprouts to brainwash Cragnons), but gives you the item you need to reach the next part of the game (the Floro Sprout), and sets up the story beat for the final act. It took until Chapter 5, but Super is genuinely off and running now. Though the world is unique to SPM, it feels like the older Paper Mario games, with Flint Cragley feeling like a new incarnation of a wacky Kolorado-like archaeologist character, as well as the inner depth revealed later on.

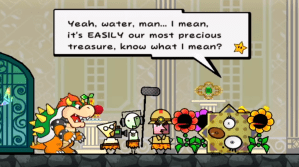

- And there’s even more. After you fight and beat King Croacus IV, the Floro-Sapiens rush in and bemoan their king wilting. They exclaim that he thought of his people first, but went mad because the Cragnons were polluting their water supply (which is a plot point set up by a small line of dialogue from a Cragnon in Chapter 5-1). After peace is negotiated with some help with Flint Cragley, you receive the Pure Heart. This theme of rival, Contrasting factions being more nuanced than they first appeared and then finding common ground, set against the appearance of another Pure Heart and thus connected to the Pure Heart’s symbolism of love, which is in itself connected to Tippi, is now set in motion.

- The chapter begins with a handful of Cragnons being kidnapped by Floro-Sapiens, and, unlike the previous chapters in which you are told where you need to go and then you just need to get there, here you spend a lot of time following these Floro-Sapiens, so a buildup is created of wondering where the Cragnons are being taken, what the Floro-Sapiens are doing with them, and where they are leading you.

- Chapter 6: This chapter is clever in terms of playing with player expectations. The set-up appears especially simple, a fight-your-way-through-100-battles world, drawing initial comparisons to the Glitzville-based Chapter 3 in TTYD. Which feels like a step-down in two ways – comparatively in-game after the more nuanced plot and story beats of Chapter 5, and comparatively from the more mystery-laden Chapter 3 from TTYD. But things start to change.

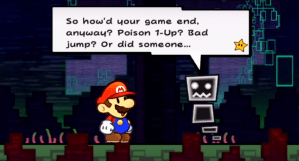

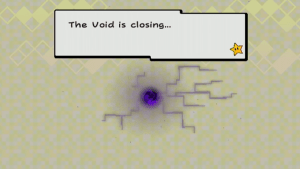

- First, Count Bleck arrives in the world to taunt the party as he watches the Void consume the world. It is no coincidence that Bleck’s first appearance in an in-game world is the world that the Void is about to destroy, further linking the symbolism of the Void with his character. And then he has his first argument with Tippi, who at this point is already linked to the Pure Hearts thanks to Chapter 3. This discussion is the first to reveal that Tippi and Bleck know each other, and is the moment where a player can genuinely say “I knew it!! Tippi is Timpani and Bleck is Blumiere.” The game plays it as such. From this point on, the characters more or less figure it out too and begin having discussions on what this reveal means, so you the player genuinely feel like you are processing your realizations along with the cast.

- Mimi serves as more of an obstacle than a story reveal, but the game uses her character here correctly, with her saying that she is not trying to beat you, she is trying to stall you.

- Then, as we know, it turns out that you are too late and the Void consumes the world. Upon re-entry, there is nothing left. Of all the Contrasts the game has set-up at this point, this one is the most stark, and the most bleak, the true personification of the stakes at hand, which themselves are a payoff to the stakes of the entire series. The potential of Grodus unleashing the demon felt cataclysmic in TTYD, but here the game is literally showing you “this is what will happen if Count Bleck wins. These stakes are real.” That you fight Mr. L again, here in this World of Nothing, is a suggestion towards an interlock between the brainwashed Luigi and the danger of this Nothing.

- First, Count Bleck arrives in the world to taunt the party as he watches the Void consume the world. It is no coincidence that Bleck’s first appearance in an in-game world is the world that the Void is about to destroy, further linking the symbolism of the Void with his character. And then he has his first argument with Tippi, who at this point is already linked to the Pure Hearts thanks to Chapter 3. This discussion is the first to reveal that Tippi and Bleck know each other, and is the moment where a player can genuinely say “I knew it!! Tippi is Timpani and Bleck is Blumiere.” The game plays it as such. From this point on, the characters more or less figure it out too and begin having discussions on what this reveal means, so you the player genuinely feel like you are processing your realizations along with the cast.

- Chapter 7: You finally find Luigi at the beginning of this chapter after Dimentio sends you to the Underwhere, and afterwards you have to restore your party by finding Bowser and Peach. Outside of these moments between our well-known characters, and the simple thematic draw of literally playing in the Mario universe’s version of Hell, the chapter actually is a straightforward trek from A to B. But because of the setting, and one key twist, the chapter gets enhanced.

- It is worth mentioning that, of the four heroes, Peach is the only one initially sent to the Overthere, whereas Mario, Luigi, and Bowser all end up in the Underwhere. Though the heroes are all on the same side in this game, it does further the series-long plot of Peach being the one who is truly pure of heart, whereas the others are all atoning for at least something.

- The chapter mission is about getting from the Underwhere to the Overthere, which adds the theme of getting from Hell to Heaven, and is reinforced mechanically because you start out having lost most of your party and, as you journey upward, slowly restore them. Just the settings themselves add a Contrasting element. Also, it is interesting that the Overthere, when it is finally revealed, isn’t an area of immediate peace, due the Skellobit invasion. This suggests that a place of absolute bliss doesn’t exist, and that danger can always be around the corner.

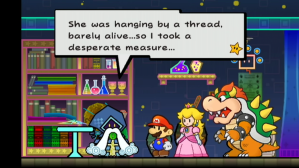

- The twist: While playing, I noticed that, compared to the earlier games, there are far less Important Items to acquire within chapters. There are less instances of items you find on your way, outside of the Pure Hearts, that then turn out to be significant in solving mysteries. But then there is Luvbi. She is introduced as the spoiled daughter to Jaydes and Grambi, so there already is an interesting setup of wondering how the leaders of Hell and Heaven came to create her. The payoff? That she is actually a Pure Heart, and the Luvbi personality was created in order to protect it. So, she is connected to this merging of two Contrasts, having come together for the greater good of protecting the Pure Heart, but, because Jaydes and Grambi came to love her as their daughter, it suggests that this merging is connected to love as well. Because Luvbi ceases to exist once she returns to her Pure Heart form, it also suggests that love can be sacrificial in order to save the world. All of this not only builds off of fringe themes from TTYD, but also foreshadows the end of the game.

- It is interesting that Chapter 7 doesn’t have any appearances of Count Bleck’s minions, choosing instead to focus on the heroes and the themes connected to them before sending them off for Chapter 8’s climax.

- It is worth mentioning that, of the four heroes, Peach is the only one initially sent to the Overthere, whereas Mario, Luigi, and Bowser all end up in the Underwhere. Though the heroes are all on the same side in this game, it does further the series-long plot of Peach being the one who is truly pure of heart, whereas the others are all atoning for at least something.

- Chapter 8: Chapter 8 is all about payoffs, mainly thanks to the aforementioned moments of local symmetries, which also serve as Interlocked characters.

- Comparisons between Bowser and O’Chunks, and then Peach and Mimi, only work because the personalities of the minion characters have been set up and reinforced well enough.

- Then comes the moment when Dimentio offers to side with you in defeating Count Bleck, claiming that he was helping your mission the whole time in terms of finding someone to stop him. At first glance, this is believable, and you more or less have to trust your instinct that Dimentio does not have a wholesome personality. This works as a good red-herring, because it gives us an answer to possible suspicions about Dimentio’s motivations, but leaves you wondering that there are more to his plans than just one battle with Luigi.

- The final battle with Count Bleck gives you the payoff of seeing our heroes come together (which we expect), and Count Bleck being defeated (which we expect). Every game in the series has featured a climactic moment like this, where the magical MacGuffins, revived by the heroes, defeat the Big Bad’s invincibility and help aid in the Big Bad’s defeat. But then, by giving us what we expect, Dimentio’s final reveal and his use of a brainwashed Luigi (using a hidden Floro Sprout no less, set up by Chapter 5) comes across as a genuine twist on top of what we expect. Like any good mystery, the reveal doesn’t come across as a left-field cheat, given that there are enough foreshadowing moments to back it up, but with the information hidden just enough to be a surprise.

- It is then a nice payoff that the Pure Hearts are revived twice during this sequence, first by your party and then again by Count Bleck and his minions. Suggesting that love and respect can be found both on the side of Light and the side of Darkness, and that siding together for the greater good is very much possible.

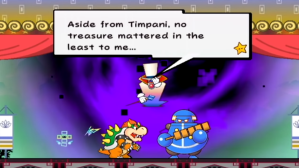

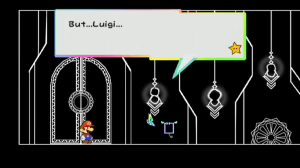

- Lastly, after being set up character-wise by the Blumiere/Timpani interludes, and thematically by Luvbi’s story, Count Bleck and Tippi need to use love to merge their two Contrasts and sacrifice themselves to save all worlds. The payoff to the series theme, and these two characters that personify far more than what initially met the eye.

- Comparisons between Bowser and O’Chunks, and then Peach and Mimi, only work because the personalities of the minion characters have been set up and reinforced well enough.

- Prologue: Bowser and Peach (two people of great Contrast who will later end up on the same team) are forced into marriage. We are introduced to the wedding chapel locale (which will return in the game’s climax), Luigi as a character that wants to help but is unsuccessful, as well as the initial character personalities of Bleck, who wants worlds to end, as well as Nastasia, his devoted servant. Later so, Tippi and Merlon are introduced when Mario is brought to Flipside.

-

Notice how, even more so compared to TTYD, these interlocked moments enhance both plot reveals and thematic depth. Even more so because the Blumiere/Timpani interludes in-between chapters set up their characters through a slow thematic story that takes its time to play out.

But also notice how comparatively simplistic the first few chapters are, before the payoffs to the macro-level set-ups begin to be revealed, and before the game starts merging its macro-level characterizations with deeper in-chapter mysteries, plots, and Contrasts. This combination of straightforward early levels with the mechanics that feel jarring for enthusiasts of the series is what makes the first half of the game drag more than the second.

Keep in mind: in the early levels, the mechanics are jarring only when SPM is placed as a sequel to the earlier games. For the most part, if a boss is easy, there is often a narrative reason to it, being O’Chunks genuinely being weaker than he believes in Chapter 1, or Dimentio sizing you up rather than fighting you in Chapter 3. The issue of the non-RPG mechanics diminishing the characters in boss fights actually comes up later, first with the two Mr. L fights, and then especially with the last two chapter bosses, Bonechill and Super Dimentio.

Again, this is the issue of the game. As strong as the Deep Interlock becomes, the early chapters are so straightforward that it feels jarring for fans of the series. The later chapters have a story that deepens greatly, but then when the mechanics don’t match this depth, it hurts.

9 – Contrast: YES. As stated in Positive Space, our main heroes feel and look different from the rest of the worlds we visit (i.e. bright colors on blacker shapes). Even when we’re not in Castle Bleck, the growing Void behind us almost always contrasting our shape and color with the dark purple it emanates. Thematically, there is less Contrast in-world…. UNTIL you reach the later Chapters, as discussed above.

In Chapter 5, the Cragnons vs. Floro-Sapiens plotline invites conflict but at the end wants us to see a bridge between them. Sammer’s Kingdom at first seems very basic, but it’s still a world brimming with life, and the Contrast is between this lively environment and the nothingness that follows after the Void destroys it. The Underwhere is in direct Contrast to the Overthere… but again – we are meant to see these two factions coming together to love personified of Jaydes/Grambi creating Luvbi at the center.

Then, there is the macro Contrast between Flipside and Castle Bleck. Flipside could be contrasted with Flopside… and it kind of is in a very direct way, with characters on opposite ends saying opposite things… but from a thematic level, Flipside/Flopside are one and the same (they are more of a symmetry), and the true contrast is between your hub vs. Castle Bleck. Flipside/Flopside are both very well lit with a lot of light, white colors, while Castle Bleck’s background is almost all black with specks of white and Void purple.

Then there are more mini-contrasts, such as Bowser vs. the rest of the party (who starts off as an easy Contrast given your history with him but then joins you), as well as Luigi vs. Mr. L, inviting us to see differences in their personalities. See a pattern? The only contrasts present are the ones we especially need to be paying attention to.

And the fact that there is no true pattern with regards to Alternating Repetition suggests that we are meant to be looking at these Contrasts and Patterns from a more macro level, which do not become evident until later in the game.

But they do become evident, as the game speaks a lot about finding that sense of peace and love at the center of what appear to be Contrasts, even if it means being sacrificial.

10 – Graded Variation: There is some evidence to change overtime, as the Flipside denizens have dialogue that changes, though far less in between chapters compared to their Toad Town and Rogueport predecessors. Still, they do experience mini-changes and indeed express fears regarding the end of the world if you speak to them before the final chapter. Additionally, and most especially you feel graded variation of the Void growing overtime. Lastly, as you piece the backstory together, you can feel the sense of time growing in the Blumiere/Timpani backstories, especially when contrasted with the present day.

11 – Roughness: Though the chapter settings are more unique compared to the Mario canon, these worlds feel more black-and-white, less rough, with very few NPCs echoing the landscape. Initially, you thus feel like the game is lacking here. In-world characters like Francis are exactly as they seem, same with Squirps (yes, you find out that he’s the prince of a space kingdom, but it doesn’t signify a deeper personality or a character arc). Unique, yes. Complex, no.

But again, as the Chapters increase, the Roughness in the thematic and character areas that matter become apparent. Bowser goes from villain to joining you (which reflects a coming-together of him and Mario/Peach, who have always been his major Contrast). Roughness. Luigi has more Roughness than you’ll ever see – hero, brainwashed villain, hero, villain again. There is Roughness in the Cragnon/Floro-Sapien plot. Roughness in the true meaning of Luvbi’s origins. Roughness in O’Chunks and Mimi. Roughness, kind of, in Dimentio in that you slowly learn that he is more cunning/evil than he seems.

And, of course, sublime Roughness from both Bleck and Tippi. Again, Bleck at first feels like a standard “wants to end the world” villain. And Tippi is a basic “guide” character. They’re not.

But notice that I also talked about the same examples in the Contrast section, as the game is all about looking at what appear to be major Contrasts and seeing the union between them. Because there are less gradations in the worlds, the game at first FEELS very black-and-white until time passes and you see the Contrasts and the thematic Roughness the game is trying to talk about.

One can argue that the theme of hidden depth is reinforced by the mechanics because the 2D/3D switch does reveal hidden depth that you didn’t initially see. However, this doesn’t carry over to the battle system, and again, it is sad when characters like Bonechill or Super Dimentio appear to have hidden depth but then, when mechanically fighting them, they don’t.

12 – Echoes: As stated earlier, the game is about Light and Darkness coming together in the end, and this theme is Echoed in all of the examples mentioned above. And with each Echo, we get closer and closer to the Strong Center, thematically.

Unlike previous Paper Mario games (above), Peach isn’t the echo of the theme. We might initially think that she is, due to the set-up of the game, but once she escapes before Chapter 2, even though we know she can indeed be an echo of what the Pure Heart is, someone else can be as well. It is no coincidence that, not long after Peach joins your party, Tippi is kidnapped and reveals a Pure Heart from her affection when you save her, suggesting that Tippi is an Echo of the Pure Heart.

This is reinforced again when Luvbi is revealed to be a Pure Heart, and then reinforces the game’s core themes of union between Contrasts, and sacrificial love at the center.

Already at this point, we have seen the Cragnons and Floro-Sapiens (factions that appear to hate each other) find a way towards nuanced peace that is followed by you receiving a Pure Heart, which suggests that finding this peace is necessary. Jaydes and Grambi then appear to be another case of Contrasting settings. So it is no coincidence that the location of the Pure Heart exists at the center of their union, personified by Luvbi, as this payoff has already been foreshadowed.

What is more prevalent in terms of Luvbi is that, in addition to echoing the Cragnon/Floro-Sapien theme of coming together towards peace, with Luvbi there is the element of love. Because while her parents constructed her in order to protect the Pure Heart and fight for peace, they grew to love her. And with her ceasing to exist by returning to Pure Heart form, the game is suggesting that love sometimes needs to be sacrificial in order to save worlds.

At this point, you can see where the game is going simply through the echoes the game has set up.

Because we know that Tippi is connected to the Pure Hearts, and represents this sense of love, light, and affection that is not especially dissimilar to Peach. She is connected to the setting where you first meet her, Flipside, which is your hub world that is whitely lit and is the world you that has the most pathos to it. It is the world most directly associated with, well, life in this universe at its most basic, and it is connected to Tippi.

At the same time, Count Bleck is connected to the Chaos Heart. He broods in a blackly-lit, dark room that has barely any elements of light. He is connected to the Void and the threat of all worlds being destroyed, echoed by his appearance in Chapter 6 that precedes the destruction of Sammer’s Kingdom. If Tippi is the echo of light, Bleck is the echo of dark.

But wait. We’ve already seen echoes of light and dark come together already in this game. Peach and Bowser (the most basic echoes of light and dark) came together early on. Then the Cragnons, whom we thought were the good guys, had to make peace with the Floro-Sapiens, whom we thought were the bad guys, with nuance in between. Then Jaydes and Grambi came together to create Luvbi in order to protect the world, and then their love was echoed when she allowed herself to disappear in order to help.

Because by the start of Chapter 8, we know who Bleck and Tippi are, we know that that possibility of a union exists and can exist, and though we may think we need to defeat Darkness as Light (which is what we had to do in TTYD), the game has been telling us that it is really about finding a union between the two – the Strong Center.

I read another pro-Super Paper Mario article that talks about how, yes, Bleck and Tippi exist at the center of the story, but the game, which presents itself as “a tale of love” from the beginning, is paying just as much attention to the love that exists surrounding Bleck and Tippi [2]. That their sacrifice, an epitome of romantic love, is painful for the other characters to witness (and thus painful for us) because these characters lose people whom they consider true friends. That love of friendship, and all the other kinds in between, may not be as front-and-center as Bleck and Tippi, but is just as nuanced and important considering the rest of the game’s themes.

Then who is the true evil? Nothingness, and this is echoed by both Mr. L and Dimentio. When Dimentio has his battles with you, he transports you to a pure green realm. And the enemy you fight in the World of Nothing is Mr. L, your green adversary who represents the potential for egoistic apathy, like Dimentio. Except that Dimentio, unlike Luigi/Mr. L, doesn’t have his kinder and darker personalities as separate entities. With Dimentio, there is no love hidden underneath, just nothingness.

Finally, it is worth touching upon the game’s music as echoes of its narrative themes.

Count Bleck’s theme music (and later his interlude theme and final battle theme) reflects a dark undertone. These themes, especially the last one, reflect a dark, choral feel reminiscent of other dark themes like the Shadow Queen’s. Contrastingly, the theme of the Pure Hearts is a theme of light and hope, reminiscent of the Crystal Stars. And, as stated earlier, the peaceful theme “Memory” which details Blumiere and Timpani’s is one of utmost peace. Flipside/Flopside, though pitched differently, are also themes of going about your life in a peaceful way; different from each other, but still daily living.

The most menacing themes, those of the World of Nothing, Mr. L, and Dimentio are more atonal and dissonant, and, when these themes are extrapolated into boss fights, like the Brobot Battle or the climactic Ultimate Show, they become chaotic, fast-paced, and messy. This links these symbols of nothingness and malice with a sound-related feel of chaos.

13 – The Void: Well, this one is literal. That’s a physical representation in this game, which we think is representative of the Dark echoes that we see in the game, but what the Void actually represents is the nothingness behind it, because that is what we see in Chapter 6. Because the presumed “dark” characters are not the enemy, as we see. Nothingness is. Dimentio, the true enemy, is dangerous because he doesn’t have a heart and believes that his aspirations for world destruction is part of a fun time. Characters that feel too deeply and do bad things as a result can at least be reasoned with, and brought back. The Void spends the entire time of gameplay growing in size, in the same way the void inside Count Bleck’s heart has been growing in size ever since Timpani was taken away.

But, as long as it hasn’t erased what came before it, the Void can be reversed, in the same way Count Bleck’s pain and hatred can be reversed. Like Merlon says, “To feel sadness is to live… But as long as you are alive, the future is a blank page.” The sadness doesn’t have to consume you.

14 – Inner Calm: There is a TON of emergent narrative complexity. Again, it says something that the key moments when the narrative is meant to be at it most emergent and revealing (the Blumiere-Timpani interludes) come with the most calming music. Which both reflects that inner calm between dark and light that we want to feel and the inner calm we’re fighting for in-game.

It says something that, in terms of the world and the basic plot, it is not as emergently complex as TTYD. Unlike TTYD, in which the lore about the Shadow Queen and the nuances of the X-Naut plot are mined out slowly (i.e. outside of rescuing Peach, at first, you don’t know what will necessarily happen if you love), in SPM, the stakes are very clear from the beginning. Get the Pure Hearts to stop the Chaos Heart and save all worlds.

Where the emergent complexity comes in this game is in the characters. Which, again, is harder to see initially. In a sense, this curve is almost too steep. In the beginning, there is a lack of complexity that is almost unnerving. But as the story progresses, the character complexity becomes so great that it becomes almost too strong for the game’s mechanics to shoulder.

15 – Not-Separateness: Like TTYD, the worlds are not all physically interconnected (even less so here), and are much more bounded, but they are connected by this theme of saving worlds by bringing what appear to be Contrasts together. And, this is an area where the mechanics do support the game, at least somewhat, in playing around with the status of your party. After Sammer’s Kingdom is destroyed and then Dimentio sends you to the Underwhere immediately afterward, your party is scattered and thus all of the mechanics you had gotten used to (like using Peach to fly and Bowser to deliver massive damage) are taken away. So, at the main narrative point where things feel the most scattered, so do the mechanics. Then, in Chapter 8, when you lose party members as you progress deeper into Castle Bleck, you also feel the loss of the mechanics again, and the stakes then feel higher.

But most especially, the game plays around with having Tippi be separated from you on multiple occasions, first when Francis kidnaps her, then when she falls to the ground and has to be revived by Merlon for a time after Chapter 4, and then when you are lost in the Underwhere. Here, the mechanic of being able to look around for clues is lost, so the game is reinforcing the importance of Tippi’s presence in your party by briefly taking her away at times, which is clever given her role as half of the game’s Strong Center.

Final Thoughts

So there we have Super Paper Mario. Let’s give it credit. It tackled a new RPG subgenre combining platforming and RPG elements, and managed to showcase an impressively deep story in the process, while allowing series-long thematic arcs to reach their apex. Most people know that the story in this game is sublime and that the mechanics needed a little work. Heck, even with just some tweaking with the difficulty levels of the later bosses, the platforming mechanics could still work without genuinely harming the narrative stakes. One just can’t help wanting more after finishing the story.

For more analysis on Super Paper Mario, please read my analysis of the game in the direct context of the Paper Mario series as a whole.

All things considered, I am glad that I replayed this game again. Hopefully you can find something out of it too. If you have, thanks for playing!

[1] Jesse Schell, The Nature of Order in Game Narrative, GDC 2018, https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1025006/The-Nature-of-Order-in

[2] Altermentality, The Tale of Love: A Super Paper Analysis, Deviant Art, https://www.deviantart.com/altermentality/art/The-Tale-of-Love-A-Super-Paper-Analysis-295194808

The Rest of My Mario Narrative Series

The Greatest Mario Story Ever Told (and Why It Still Isn’t Perfect)

Challengers to Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (Expanded)

Paper Mario: The Origami King – Give it a Chance to Make an Impact

On Nintendo’s Nostalgia-Based Model

The Super Mario Bros. Movie (YouTube Review)

Additional Analysis

The Controversy of Super Paper Mario – Nintendrew, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=euZscfTm1qU

What Makes Super Paper Mario A Paper Mario – SuperMarioT, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7LZ9jamwFg&t=415s

The Lore-Axe: Super Paper Mario Complete Lore – Game Domain, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fu3p0w3lLDA

Foils in Super Paper Mario – Alison, http://sheesania.com/foils-in-super-paper-mario/

Bad Game Design – Super Paper Mario & Color Splash – Snoman Gaming, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JvjmgnLTKKQ

For Fun

Super Paper Mario Musical Bytes – Complete Package – Man on the Internet, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Fm1Teu2cY&t=8s

For the uninitiated, these patterns can be described as such [1]:

For the uninitiated, these patterns can be described as such [1]: