Five years ago I wrote a blogpost titled “Trying to Address My Love of Longform Play” and made posits about why certain games, like Mafia, that have extended “rounds” to them appealed to me more than one-off/one-round games, but also why when playing sports video games, playing one game was enough for me. That I preferred emergent narratives.

At the time, I thought about how in sports video games, the narratives of the players you are playing as are already built into the singular games, and thereby could be enough maybe as if the game you just played were fanfiction.

But that got me thinking more indeed about the narratives that do emerge from sports games, seasons, careers, at the macro and at the highest level, particularly in that of the three sports I probably pay the most attention to all season long: basketball, baseball, and tennis.

This became apparent given that the year I wrote that post, 2019, proceeded to have, retroactively, possibly the longform climaxes of the respective eras of those three sports, which feels especially apparent as we have gotten deeper footing into the 2020s.

(NOTE: See the bottom of this post for the charts)

The Fall of a Dynasty

In basketball, the mighty, dynastic Golden State Warriors took their stride into that year’s playoffs, now with an injured LeBron out of the tournament entirely, and appeared to have a free path towards a three-peat championship with no one realistically to even claim to stand against them.

However, the team began to show cracks as early as the first round of the 2019 playoffs, being taken to six games by the undermanned Los Angeles Clippers and appearing over-reliant on Kevin Durant bailing them out of poor shooting games. Only for Durant himself to go down with a calf injury in Game 5 of the Western Conference Semifinals rematch against the Houston Rockets… and for the Warriors to immediately recapture their pre-Durant form and win six straight games enroute to another Western Conference title, restoring their previously shaky aura of invincibility.

Meanwhile, the proverbial “butts” of the Eastern Conference and of the fabled “LeBronto,” the Toronto Raptors, were free from LeBron James and had one more shot to prove the thousands of doubters across the league wrong.

Having acquired Kawhi Leonard in the offseason, the lovable losers shook off their playoff demons and survived multiple clutch series against the stacked Philadelphia 76ers – punctuated by one of the greatest game-winners in NBA history – and the top-seeded Milwaukee Bucks.

And as the Eastern Conference’s greatest underdog-turned-clutch-team faced off against a dynasty, the storylines began to write themselves.

Here came Kawhi Leonard, Danny Green, Serge Ibaka, and Marc Gasol – descendants of the San Antonio Spurs, Oklahoma City Thunder, and Memphis Grizzles, probably the only three teams outside of Houston to give Golden State a real scare during their dynasty years in the West, now united on a new team that suddenly had “destiny” written all over them.

But as the fight got underway, it was less about the play of these superstars and more about a Warriors collapse from within.

Already vulnerable without Durant, the Warriors lost Klay Thompson to a leg strain in Game 3 of the NBA Finals, and then got outplayed at Oracle to set up an elimination game in Toronto.

Durant strode through the doors as a possible savior – and all the narrative implications it held: the Warriors, now whole and fully invincible, coming back from down 3-1 in an NBA Finals, with Durant finally proving himself as the most valuable player on the team. Only for Durant to go down for good with a torn Achilles.

The fighting Warriors survived Game 5 and seemed poised to push the Finals to Game 7 on will alone, with “Game 6 Klay” possibly enough to get them over the line again just like in 2016.

But there goes Klay going down with a torn ACL in the back half of the third quarter.

Still, the Warriors fought to end. But after one last missed Stephen Curry three that could have gotten them to a winner-take-all, the Raptors survived… almost Shakespearean in how it all played out.

The “butts” of the league, now champions, with symbolic remaining players of prior conquered foes, having ended a dynasty, even though in more ways than one said dynasty collapsed from within.

The Underdog Run that “Saved” Baseball

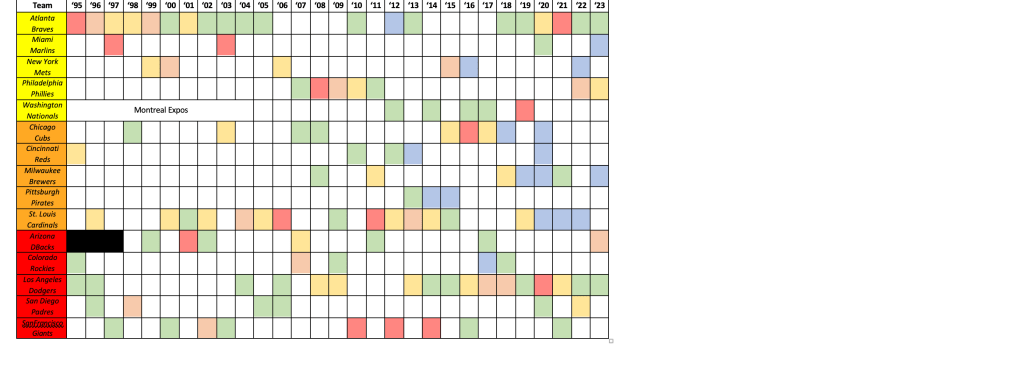

On the other side of the coast, baseball geared itself up for the greatest month of competition every year, at the culmination of a decade that, whilst dominated somewhat by staple teams like the Boston Red Sox and the St. Louis Cardinals, more or less had been defined by some kind of improbable and/or curse-lifting playoff run seemingly every year.

The even-year San Francisco Giants runs, though seemingly dynastic on paper, actually held the form of underdog runs every year, with the Buster-Posey-led, scrappy workhouse team outmuscling “better” teams in the Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals, and Washington Nationals each time.

The 2011 champion St. Louis Cardinals and 2018 NL-pennant-winning Dodgers actually occurring during “off” years and featuring better clutch performances than their years of respective better records.

And then, of course, the Curse-busting miracles of the 2015 Kansas City Royals, 2016 Chicago Cubs, and 2017 Houston Astros, to take nothing away from the magical runs of many their competitor, the 2015 New York Mets and the 2016 Cleveland (then)Indians.

As the dust seemed to settle on this wild decade of improbable runs, parity across both leagues, and new winners not seen in decades, a new shape had become clear:

The Houston Astros, after winning the title in 2017, were approaching the precipice of a true dynasty, entering the 2019 playoffs looking to win their second title in three years, and, unlike the scrappy Giants, carrying regular-season dominance in 107 wins to possibly justify the D-word.

Their biggest rivals seeming to be the new-and-improved 103-win Yankees, looking for revenge after their 2017 ALCS defeat, and, now resembling their more dominant 2017 form and seemingly having shaken off their “choke” years of 2013-15, the 106-win Los Angeles Dodgers.

The Astros and Yankees indeed chartered a collision course in the 2019 ALCS, with the Astros walking off enroute to the 2019 World Series after Jose Altuve matched DJ LeMahieu’s heroics with magic of his own.

But on the National League side of things, once again, the fabric of expectation came undone with another Cinderella run, albeit maybe from baseball’s MOST unexpected source.

Many the runs of the 2010s came from teams that were making their first push with nothing to lose, like the 2010 Giants, 2014 Royals, 2015 Mets, and 2016 Indians. Other runs came from teams that had already sniffed a modicum of success and were looking to double down on it or expand it, like the later iterations of those pesky Giants, 2016 Cubs, 2017 Astros, or 2018 Dodgers.

But the 2019 Washington Nationals were completely different animal.

Like the Toronto Raptors over in the NBA, the Nationals had been the overt, abject, choke-artist “butts” of Major League Baseball the entire decade, compiling regular season dominance in four out of six years, only to fall apart in the NLDS, usually in pretty brutal fashion.

Now without Bryce Harper and stuck in the NL Wild Card Game, history seemed like it was about to repeat itself, as the nigh-unhittable Josh Hader of the Milwaukee Brewers (looking to expand themselves after an NLCS run in 2018) strode to the mound with a 3-1 lead in the bottom of the 8th inning.

But after several fluky plays, massive two-out hits by Ryan Zimmerman and Juan Soto, and an even-more-massive error by Trent Grisham, the Nationals had the lead.

Baseball’s decade-long choke artists had flipped the script and were barreling their way towards Hollywood.

Where they would double down on their heroics in the NLDS, toppling those 106-win Dodgers in a 10-inning Game 5 thriller, featuring a go-ahead grand slam by Howie Kendrick and the Dodgers – and, unfortunately, Clayton Kershaw – reverting to their own choke days of 2013-15.

Now resembling an even more ironclad version of the 2015 New York Mets, the 2019 Nationals steamrolled their way past the Cardinals in the NLCS and prepared for an even bigger foe in those nigh-dynastic Astros.

After a series of weird games in which the road team won every game, the Nationals found themselves down 2-0 in the 7th inning of Game 7, with a dominant Zach Greinke still on the mound, but with a gutsy Max Scherzer performance keeping them close.

Anthony Rendon homered, and, after a patented Juan Soto walk, Howie Kendrick, NLDS hero and NLCS MVP, coming up. And we all know what happened next.

The clang of Kendrick’s foul-pole-smashing, go-ahead home run signaled one of the top ten greatest World Series plays in MLB history (at least by Championship Win Probability Added), and the Nationals – choke artists turned clutch performers turned outright world beaters – never looked back enroute to their first championship.

In the offseason, with the reports emerging that the Astros led a cheating scandal in both 2017 and (likely) 2019, many pundits claimed that the Nationals denying the Astros the power of a championship saved the integrity of the sport itself.

Already representative of the many 2010s Cinderella runs in maybe their purest form, the 2019 Washington Nationals were now deemed across the country as David-beating-Goliath heroes.

The Last Dance of the Big Three

Not to be outdone, over in the clay, grass, and hard courts, two decades worth of tennis came to a head.

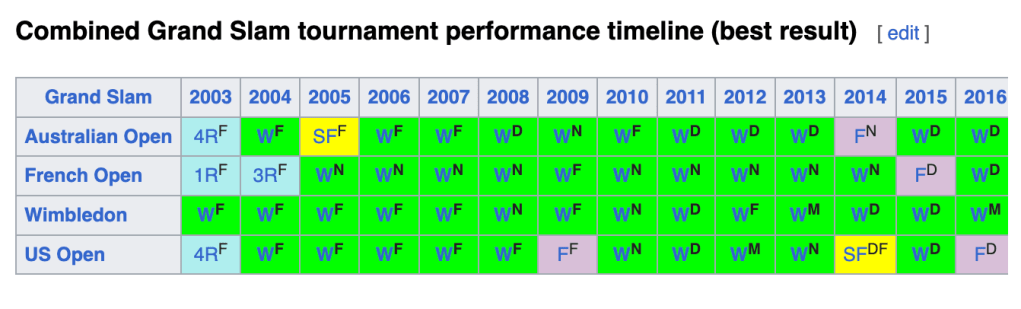

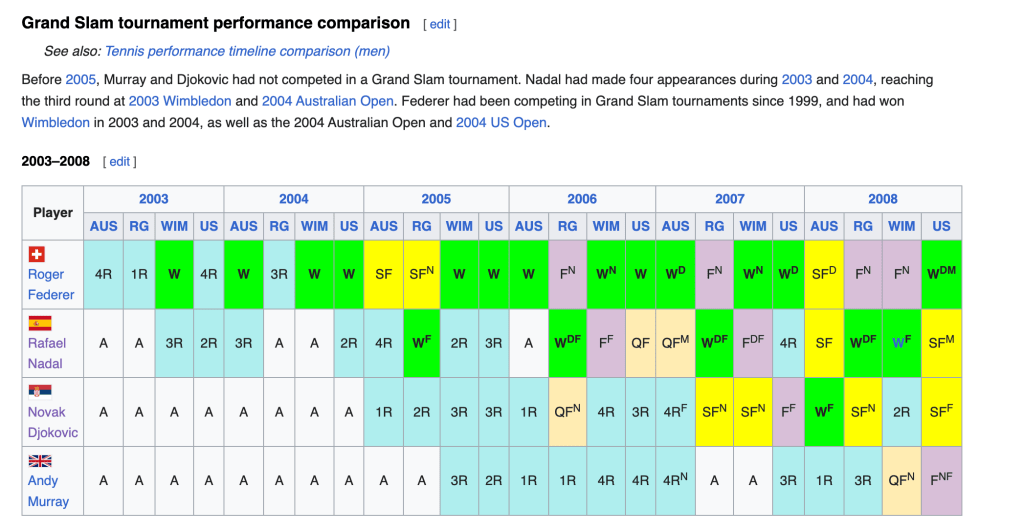

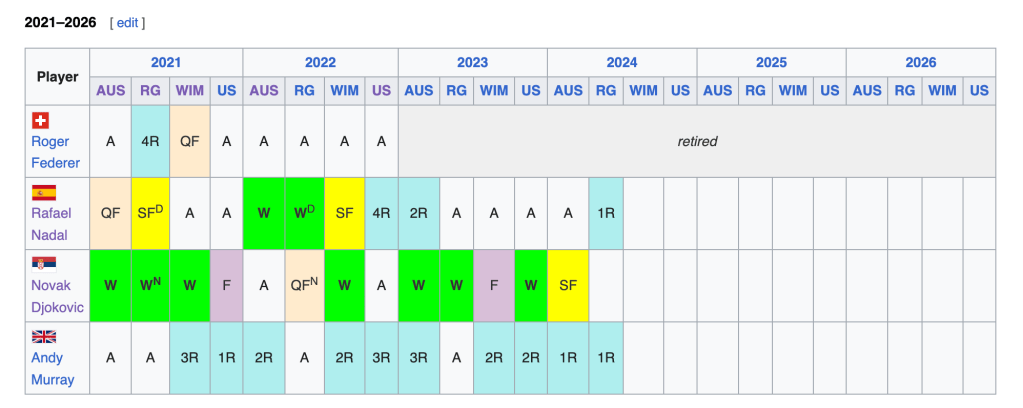

Since the mid-2000s, the sport had been dominated – outside of a few tics here and there – by three men (Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic) and one woman (Serena Williams).

On the ladies’ circuit, Serena’s era of overt and abject dominance had waned after her 2015 peak and 2017 pregnancy, but she remained the biggest and most dominant force on tour. Retroactively, Serena’s runs to the 2019 Wimbledon Final and 2019 US Open Final are her last glimpses of deep competitiveness in Grand Slams, indeed unable to catch Margaret Court and hold off the next generation represented by Bianca Andreescu.

So we remember Serena’s 2019 season as, in some ways, the denouement of her career before full closure in 2022.

But on the mens’ side, the tension was even greater.

After giving way to Novak Djokovic dominance in 2015, the era of Federer and Nadal had seemingly come to an end, with Andy Murray and Stan Wawrinka left to contend with the mighty Serb.

But like dual phoenixes rising from the ashes, both Federer and Nadal ascended to the peak of the sport again in 2017 as a wrist injury sapped Novak’s craftiness and ability to contend at the highest level.

But not to be deterred, he would join them again in 2018, winning Wimbledon and the US Open after “Fedal” had alternated Grand Slam victories the previous year-and-a-half.

So 2019 featured all three of them at the height of their abilities – a cut above everyone else, all at the same time – for one last rodeo before injuries to Federer’s knee (2020-21), COVID complications to Novak’s “availability” (2022), and injuries to Nadal’s foot, abdominals, and hip (2021, 2023-24) would put an end to competition between the three of them for good.

But from the 2019 Australian Open all the way through 2019 Wimbledon, it indeed was the Last Dance of the Big Three.

Novak – having already passed the Nadal test on grass the previous year – would first outplay the Spaniard at the 2019 Australian Open. Then, at the 2019 French Open, Nadal would once again prove his “King of Clay” fighting spirit in abysmal conditions against Federer.

Finally, at Wimbledon, Federer would get Nadal back on his own favored surface one last time, seemingly on course to make it a “favored surface” split as he appeared the fitter opponent for much of the subsequent final.

Only for the Serb to muster one of the greatest “mental strength” comebacks in all of sport in what many deem the greatest final of all time.

Federer would get a “tiny” bit of revenge against Novak at the 2019 ATP Finals, but the Serb had nothing left to prove at that point in time.

Though Novak and Nadal would get a couple more cracks at each other in the 2020-22 French Opens, it remains 2019 as the peak (and thus climax) of the decades-long era of the Big Three.

Transitions in the Present Day

It almost was like as if COVID put a hard stop on any continuing narratives left over from the 2010s, and as the aforementioned luck would have it, these sports themselves would shift anyway once the calendar turned to 2020.

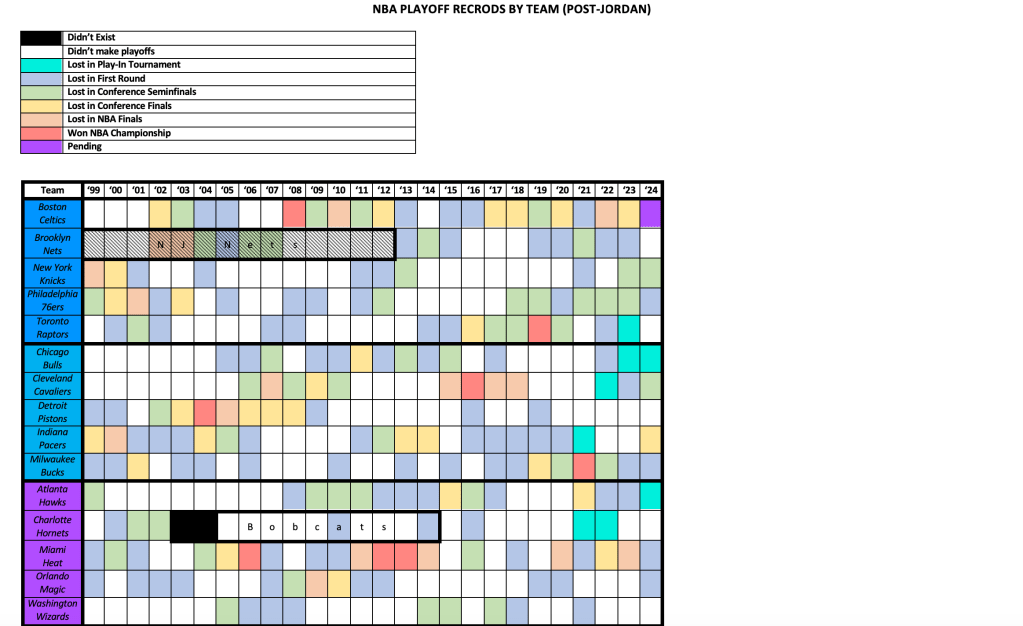

In addition to aforementioned changing of the guard in tennis, basketball would see a return to greater parity come the 2019-20 season, with “Big Four” Golden State Warriors dynasty over and superstars zooming around to different teams as if by lightning speed.

No wonder that we have seen different combinations of NBA Finalists every year since 2019, with Miami Heat (2020, 2023) and Boston Celtics (2022, 2024) being the only teams to make multiple finals regardless, and no previous-year champion even making it to the Conference Finals.

Over in America’s pastime, for a moment there seemed to be a repeat of that magical 2019 Nationals run. After the COVID-shortened season acted as more of an exhibition tournament than a full season that allowed the Dodgers to reclaim a bit of dignity, two more NL East teams would take cracks at the mighty Astros.

However, by then, the 2021 Braves were a perennial contender and their run resembled more of a 2011 Cardinals or 2018 Dodgers run, in a which a contender finds their juju in their “worst” season enroute to a title. And the 2022 Phillies, though improbable, were more of a “first rodeo” team à la the 2015 Mets and 2016 Indians.

And the Astros, with a major Dusty Baker assist, had done some measure of rehabilitation on themselves, so both World Series had more of a straightforward underdog-versus-favorite vibe and less of a miracle team representing good defeating a would-be dynasty that represents evil.

And if 2023 were any indication, the equally improbable runs of the Texas Rangers and Arizona Diamondbacks, combined with the back-to-back shaky playoff performances of division winners post-Wild-Card-expansion, means that we are entering an era of complete parity, similar to the NBA.

In the same way, as of this writing, Novak’s recent meniscus injury suggests a complete turning over of tennis to the next generation in Carlos Alcaraz, Jannik Sinner, and their peers in the months and years to come, even though watching both the Serb and Rafa fend them off for the better part of three years was indeed a sight to behold.

But potential narratives in the future do abound.

Alcaraz and Sinner have already positioned themselves as the next faces and members of the foremost cornerstone rivalry of the sport. As well as separation between them and the “next tier down” level of slightly older players – Daniil Medvedev, Alexander Zverev, and Stefanos Tsitsipas – who each may have a signature tournament win to their respective names (the 2021 US Open for Medvedev, 2021 Olympics for Zverev, and 2019 ATP Finals for Tsitsipas) but face an uphill climb in future years against the youngest faces of tennis.

In baseball, the Phillies seem completely determined to leave no doubt this time around, transforming themselves from “the scrappy team” to the team in the NL East for the 2024 season, and a (maybe) future date with those billionaire Dodgers who are looking to rebound from three playoff choke years in a row (again).

To say nothing of the 2024 Yankees, Guardians (used to be Indians), and Mariners, the former running back a retooled Aaron-Judge-led team for what feels like the tenth time, and the latter two looking to take on a 2016-Cubs-run as a semi-veteran-team looking to expand on recent histories of small-tier playoff successes.

And finally, we come to the NBA, as the Boston Celtics look to face off against the Dallas Mavericks which shapes up to be arguably the most narratively-salient NBA Finals since the fall of the mighty Warriors.

Because the novelty of two underdog teams in Phoenix and Milwaukee in 2021 produced some excellent hoops, but was so new it paled in comparison to some of the stories that came before. Or the fact that the baby-faced Celtics in 2022 were always going to be second-banana in narrative to the “One Last Time” Durant-less Warriors of 2022. Or the fact that last year’s finals held the potential of the Miami Heat being the league’s potential kryptonite to every upper echelon team in their path – only for the champion Nuggets to put such storylines to bed before they really had the chance to get off the ground.

But this year:

We have an experienced, now-veteran Celtics team with undisputedly the league’s most impressive team with its best record, back to where they belong two years after they first got there. Set up against a Mavericks team that had the league’s best trade deadline, back to where they belong two years removed from their own run in 2022.

With potential revenge series narratives for both Kyrie Irving and Kristaps Porzingis.

With “face of the league” narratives for both Luka Doncic and Jayson Tatum.

After years of feeling like the league as been in somewhat of a transition going from one grand narrative to the next, from one generation to the next, the stars are aligned for some real fireworks.

Charts

I’m not sure exactly why I wrote this post.

Maybe it was simply an excuse to gush about my three favorite sports, having seen the narratives of my childhood climax in more than one interesting way.

Maybe it was to pose thoughts, indeed, about how narratives can emerge in sport simply by playing it.

Maybe, after watching narratively-salient fictionalized sports content like Game of Zones (above), Winning Time (below left), or Challengers (below right), I’m of a deeper mindset of looking for the story in the game.

Maybe it was to make predictions about what might come next.

But maybe, maybe it was just an excuse to make some charts.

See, on the tennis side of things, I have always been interested in seeing the accomplishments of the sport’s premier names set against each other. Not just as singular lists and statistics, but cross-referential ones.

Sometimes when I am curious, I go to Wikipedia to see the statistics of Federer, Nadal, and Novak contrasted against each other.

(NOTE: This page also includes Andy Murray’s statistics, given he (mostly) was able to stay with the Big Three from 2011-2016)

And after doing some digging, I couldn’t seem to find similar charts for my other two favorite sports.

So I made my own.

What I like is that you can look for your favorite team, or team that your favorite player happens to be on, cross-reference it with other knowledge that you’re aware of, and extrapolate it out to whichever sports narrative tickles the itch at any moment.

Also that charts like these can be ongoing and expanded upon overtime.

Which I will continue to do so as the months and years continue, during which I do intend to get back to both my “Mario Narrative” series as well as my YouTube Reviews, especially with the recent remake release of Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door.

But before I do, I wanted to take an excursion into the land of my favorite sports, if only to gab about my favorite storylines that I’ve spotted over the last 10-15 years.

To say nothing of storylines that have emerged in recent Olympics, World Cups, or the other dominant US team sports like the NFL, NHL, or WNBA, which while I don’t follow as closely as the above three, I follow enough to know that narratives like the rise of Katie Ledecky, Mbappe vs. Messi, the dominance of the Kansas City Chiefs, or the likes of Sabrina Ionescu and Caitlin Clark becoming household names – all could deserve posts unto themselves.

And that’s before touching on the ongoing storylines in Golf, including the Masters-Tournament-clinching coda of the great Tiger Woods, which, you guessed it, occurred in 2019.

Realistically though, it was a chance to give myself an excuse to make charts to see many of these emergent, macro storylines set against each other in one grand image.

Thank you for reading. I hope it wasn’t too meandering.

Cheers!