Hello. About a year ago, I constructed a design blog post maintaining that Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (TTYD) was the greatest Mario story, that it built off of the Mario structure while also combining it with a multitude of rich narrative themes and characters. As part of this post, I compared this game to its potential successors and why none of them quite reached heights that TTYD did.

At the time, I had yet to play Super Mario Odyssey, but, having more time at home lately because of obvious reasons, I recently had the chance to do so (see an expanded section of my original post or more details). And I was struck by the number of similarities that Odyssey drew on from not just TTYD, but its predecessor Paper Mario (PM64). Yet, while I recognized that the game mechanically was about as sublime as a game can get, the story began to lose some steam in the second half of the narrative, with a particular fake-out at the end of Act Two irking me most, due to it promising an idea of progression in the narrative stakes, before immediately removing said progressed stakes from the story (no, this isn’t an Odyssey post, but bear with me).

From this experience, I decided to give TTYD’s immediate successor, Super Paper Mario (SPM), another try. I had just played a game with perfect mechanics but with a storyline that lost steam overtime. So why not replay the game that, in my mind, has the opposite problem?

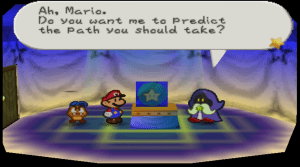

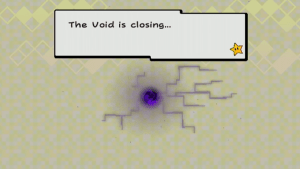

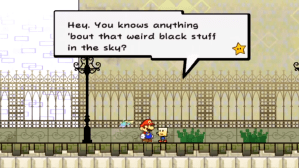

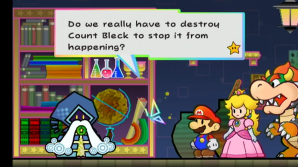

For those who are unaware, the Nintendo Wii’s Super Paper Mario tells the story of a lost prophecy called the Dark Prognosticus. At the start of the game, the villainous Count Bleck forces Bowser and Peach into marriage which unleashes the Chaos Heart. This dark artifact powers what characters refer to as The Void, a purplish, black-hole-like mass that hovers over the worlds of the game. Overtime, as the prophecy states, The Void grows in size until it threatens to swallow every world whole and erase them from existence.

Mario needs to collect magical MacGuffins called the Pure Hearts, which, if united, have the potential to counteract the Chaos Heart and stop the Void from ending all worlds. Joining him in his adventure this time are Peach, Bowser, eventually Luigi, and a series of blocky “partners” known as Pixls. The first of these Pixls is the butterfly-like Tippi, who acts as your guide like Goombario and Goombella did in the previous games. In general, Pixls replace the standard party members from the older games.

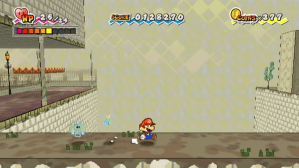

Unlike the original two games, Super Paper Mario is entirely in 2D and does not have any turn-based RPG elements, playing instead like an action platformer. Early on, Mario is granted the ability to “flip” into 3D, and this ability can then be utilized to solve puzzles and find other secrets as the story progresses.

I had major issues with the mechanics when I first played SPM many years ago, and upon the first few hours of my new playthrough, these mechanical flaws were still bothering me. But at the same time, I remembered that the storyline got more complex as the game progressed, so I continued playing…

…Wow. I somewhat remembered and knew from its reputation about how Super Paper Mario has the deepest story of the Mario lineage, but I had forgotten just how much. Whereas Odyssey began to lose momentum in its second half, Super Paper Mario simply gained more, and more, and more, until by the last frame of the game I was crying. What was this? (COMPLETE SPOILERS WILL FOLLOW)

I said in my original post about TTYD that The Thousand-Year Door makes the player believe he/she is playing a standard Paper Mario sequel shuffling through familiar locations for the first chapter or two, but then by Chapter Three spreads its wings and becomes a more complex tale filled with lore, prophecy, and examinations of power and love beyond the standard Mario/Peach/Bowser conflict we would expect from a Mario game.

SPM, in truth, for the first several or so chapters, it feels the same, but even more trimmed down. Without the turn-based RPG elements to lean on, the game feels especially minimal, and, even with the ability to switch from 2D to 3D, it feels like playing a paper version of Super Mario Bros. and, gameplay-wise, does not feel like a sequel to TTYD at all. The gameplay is trimmed, the story feels trimmed, you are not really engaging a whole lot with the blocky world around you, more so just passing through, and you fight Count Bleck’s minions once in order (like you would Bowser’s Koopalings in the older games).

Your journeys in each chapter more or less consist of you moving from point A to point B, with some discussions along the way. There are a handful of interesting subplots, like the mischevious Mimi enslaving you into manual labor in Chapter 2 to pay off a debt, or the supernerd chameleon Francis stealing Tippi in Chapter 3 and then forcing Peach into a dating simulator in order to win her back, but overall there is a lack of worldbuilt complexity that, combined with the trimmed-down controls, makes the game feel jarring. Even with the added draw of Bowser as a party member and a brainwashed Luigi as a boss, the game doesn’t really feel like a Paper Mario game.

Mimi’s Manual Labor (Chapters 2), and Francis’s Dating Simulator (Chapter 3)

Until it does. More nuanced conflicts around the world are slowly explored, and hidden depth is revealed. For example, in Chapter 5, a conflict between two races in a prehistoric world, the Cragnons and the Floro-Sapiens, is revealed to be more complex: you have been working with the Cragnons the entire chapter to rescue members of their tribe who have been kidnapped and brainwashed by the Floro-Sapiens, and their leader King Croacus IV. But at the end, it is revealed that King Croacus IV went mad and started brainwashing Cragnons in order to protect his people because the Cragnons had been dumping waste into the Floro-Sapiens’ water supply, their most precious resource. Neither side is inherently evil, we get to explore ideas of what turns someone cruel, and these nuances need to be acknowledged for the conflict to end.

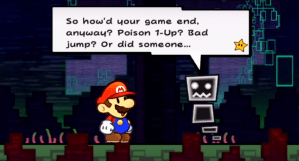

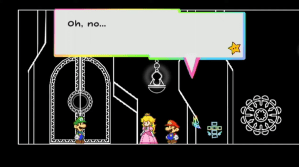

Then, the stakes of your mission are revealed in an especially brutal way when a world called Sammer’s Kingdom is destroyed in Chapter 6, and all that is left is blank nothingness. And you think, “okay, that got really dark. I’m guessing that the game will return to its normal linear storytelling now.” Nope. In the very next scene, Count Bleck’s minion Dimentio kills you and sends you to the Mario universe’s version of Hell, the Underwhere, and you have to find your way out while simultaneously finding a way to “fix” the powerless Pure Heart you found in the destroyed world, and locate the next Pure Heart at the same time.

Dimentio sends you to the Underwhere just after you witness the end of a World

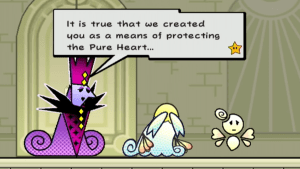

Your party is scattered and you get to know Queen Jaydes, leader of the Underwhere, King Grambi, leader of the Overthere (the universe’s version of Heaven), and their presumed spoiled daughter, Luvbi. Not only are they instrumental in “fixing” the powerless Pure Heart, but it is revealed that Luvbi is the next Pure Heart. And that even though her parents love her (and this is played for real), she has to return to her true Pure Heart form and thus cease to exist as Luvbi in order to further the cause of protecting the world. Ouch. Now the game is really bringing an idea of nuanced love being repurposed to further the cause of saving the world.

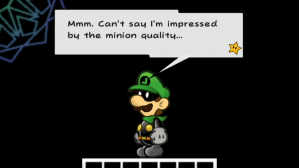

All the while, Count Bleck’s minions appear and re-appear and begin to reveal complexities that we didn’t notice at first. For example, O’Chunks looks like a brawny idiot, but is actually just a guy who wants to be “tough” and is looking for respect. The brainwashed Luigi, who goes by Mr. L, fights you twice and expresses a ton of “I am the best” egoism before he returns to being Luigi your ally when you meet up with him in the Underwhere. Is this Luigi being brainwashed, or is this a side of him that he has been repressing?

On top of that, your “guide” Pixl, Tippi, begins to express repressed pain, and we realize that what appeared to be a pared down knockoff of Goombella, mechanically, actually harbors the deeper character personality. All the while, a mysterious backstory about two people named Blumiere and Timpani is explored in text interludes, two people who were in love but where kept apart by circumstance. Eventually, if you are paying attention, you will slowly realize that these two people were Bleck and Tippi before they became Bleck and Tippi, and that this story is more than just a simple story about defeating a demonic villain in order to save the world.

By the time the ending came along (which I will get to later), I realized what this game was about: hidden depth, the nature of what turns people “good” and “bad”, and the idea that true love can genuinely save the world.

And then I realized that that is what all of the original three Paper Mario games were about.

The subtle truth is: from PM64 to TTYD and now to SPM, this series was actually telling the arc of a complete trilogy. Because yes – in SPM, the world seems more “alien”, and less nuanced than it does in the previous two games, and Mario and the rest of your party seem like they are passing through the worlds. But that was the point. Because throughout the entire series, the games had been slowly paring down the traditional narrative elements we are most familiar with, and moving Mario and his immediate allies further from their immediate comfort zone, in order to land on the thesis statement that the games were expressing all along.

From here, I will go through all three games to explore that Super Paper Mario is not just an astounding story in its own right, but that it also is the perfect “last chapter” in a trilogy of three games, paying off every established narrative thread in subtlety progressive and condensed fashion…. narratively speaking. The mechanics of SPM still hold it back, but I don’t think we realize just how close this game was to absolute veneration. Had the game simply changed one and only one aspect of its mechanics, we would most likely speak of SPM, not TTYD, as the greatest of them all.

NOTE: This post is about exploring Super Paper Mario from the lens of a trilogy. For those interested in an even deeper dive on the design details of the game, please view my post here, which applies A Nature of Order to Super similarly to how it was applied to TTYD in the original post.

Before getting into this trilogy argument, I will touch about aspects that help make a complete trilogy.

Ken Miyamoto, author and produced screenwriter at ScreenCraft, discusses the tenets of great sequels in his featured article The Ten Commandments of Writing Great Sequels. Included among these are [1]:

-

-

- DO NOT remake the original

- BUT DON’T reinvent the wheel either

- Give the audiences something new but similar

- Take the original characters FORWARD and understand that they are the franchise

- Build on the original’s mythos

- Know that a sequel is only as good as its villain

-

When looking at sequel, and especially a threequel and/or series-capper, yes, we want the themes and stakes to progress and reach their highest alongside core character development. And we want the world to expand, bringing these characters to new adventures that also utilize a familiar structure. But also, we want the themes to contract. Well-renowned series like Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter build on what came before but also contract their worlds, shrinking the number of characters or areas of travel to their most base elements, and, often, their most personal.

Even series like Toy Story or Planet of the Apes that are built off of more stand-alone adventures, with new characters in each adventure, progress their stakes while, overtime, shrinking the number of elements down to the core thematic elements and moments, if done well. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is also a prime example of a series escalating its villains and giving us the most powerful and most complex, Thanos, in the last Act.

The new Planet of the Apes series in particular is good foil to Paper Mario (light spoilers to follow): in Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011), the story is as much about the human world that helps creates both sentient apes and the Simian Flu, as it is Caesar’s rise to becoming a leader of the apes; in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014), the old world has been seemingly destroyed, and the ape world is rising in its place, but a shadow of the familiar human world still remains, and the conflict comes from people looking to exploit these worlds and those with good hearts looking to prevent war; by War of the Planet of the Apes (2017), we don’t see any expansive series of battles, but we see a distressed world at its most bleak, with very few additional characters outside of those already introduced, and the characters looking to escape before the world destroys itself.

With each movie, the human world contracts and the ape world expands, and the most direct human foil to Caesar’s character progresses from mild and kind to twisted and villainous with each movie, as the stakes grow higher. You can almost read the series, tonally, as a metaphoric progression from summer, to fall, to winter.

Now, this series deals with far more complex themes than Paper Mario does, with issues of race, extinction, and other serious real-world problems, but this idea of having separate adventures within a progressive story, while having one world contract and another expand and grow darker alongside the character development of its main characters and stakes, is an idea that Paper Mario employs as well. The new Planet of the Apes series works because even though each movie is stand-alone, each movie builds off of the one that came prior, in terms of its worldbuilding and its themes. I maintain that the Paper Mario series does the same.

Now, of course, because Paper Mario is a game series and not a film/TV series, it has to do all of that from both a narrative and game design perspective to be considered fully effective, as mechanics and story should be interconnected in games.

Snoman Gaming’s video on “What Makes a Great Sequel?”, (which ironically was covering TTYD) states that, in addition to the aforementioned traits, good gaming sequels must “try out new concepts while still retaining their identity” [2].

A Side Note on the Father of All Mario RPGs

One last point before getting to the Paper Marios: I would remiss if I did not give a shout-out to the father of all Mario RPGs: Super Mario RPG. I do not consider it to be part of the Paper Mario trilogy, and neither did Nintendo. Super Mario RPG (SMRPG) is a fantastic, unique, original game that stands by itself, and introduced Mario to the RPG landscape through nuanced battle mechanics and a complex story to boot. For more on my thoughts about SMRPG, view its section of the discussion here.

However, the original Paper Mario, which was released five years after SMRPG, does not treat itself as a true sequel to SMRPG. While it retains a handful of stand-alone elements like the idea of shooting stars being able to grant wishes, a realm where star-based beings live in the sky, and an island full of Yoshis, the game completely repurposes its characters and the rest of the setting.

Whereas Bowser teams up with Mario and company in SMRPG, PM64 treats him as the main antagonist, which, if PM64 were viewing itself as a sequel to SMRPG, would be a character regression. Some of the more wacky elements present in SMRPG – like talking moles, sentient frogs, and “out-there” villains like Punchinello or Booster – do not appear in Paper Mario. Like SMRPG, the setting in Paper Mario is still the Mushroom Kingdom, but this game’s version of the Mushroom Kingdom employs more lands based on traditional Mario archetypes, like grass land and desert land from the earlier games. Whereas Super Mario RPG’s setting feels fully novel, the setting in Paper Mario feels more familiar, which reinforces its feel of a back-to-basics storyline (see below).

This, combined the game’s reinvented aesthetics, make Paper Mario and its sequels feel especially dissimilar from SMRPG. To paraphrase Snoman Gaming, Paper Mario wouldn’t be a true sequel to SMRPG because it does not retain its identity [2]. Nintendo saw what worked and what they liked from SMRPG, and then remade the characters and the world from the ground up for a new series: Paper Mario. In some ways, they had no choice, because, from a business standpoint, they used a new collaborator on the series: Intelligent Systems, because of a soured relationship with their collaborator from SMRPG, whom retained the rights to the SMRPG world [3].

This is a part of what gives Super Mario RPG its mythos and position in Nintendo lore: there is no other game like it. But as such, for the extent of this post, it will be viewed as a game outside the Paper Mario trilogy.

Now, let’s begin by diving into Paper Mario. Keep in mind, I will not be touching on the details of PM64 and TTYD as much as Super, because I have detailed them already in my original post.

The Original Paper Mario: An Expanded Familiar World with a Simple Story

Paper Mario is your standard Mario story with a more developed world. As discussed in the original post, it is already acing the “give audiences something new, but similar” tenet [1] by using the established Mario structure to tell its story. The charm of Paper Mario in its entirety is that it is new in its expansiveness, but mostly familiar.

The first game sets up Mario as a silent hero, Luigi as the forgotten brother, Bowser as the bumbling villain that wants Peach for himself, and Peach as a distressed damsel but who has more of a mischievious side than we give her credit for. The underlying plot is Bowser stealing the Star Rod, which leaves the Mushroom Kingdom denizens feeling like their wishes are not being granted anymore, and things feel a little more hollow.

There is a wide variety of characters in this world, from Jr. Troopa to Kolorado, who are not directly connected to the main plot of Mario vs. Bowser. There are characters dealing with mysteries and happenings in their own lives, from the mysterious Moustafa in Dry Dry Outpost to the Shiver City Mayor who nearly dies, whom you speak with on your quest but who are mainly just going about their lives and whose plot connections are more world-related. There are characters who want to do right by themselves and look up to Mario as a symbol in order to do so. Even if these characters don’t shape the plot, they expand the world being created by the game.

By the end, peace is restored, Bowser’s minions have been removed from the kingdom, and Mario and Peach are happy.

Original PM64 feels and is Mario’s story. You can make an argument that it is the only story where it actually feels like there are stakes for him /personally/ because, for Bowser, he /has/ made it personal. Additionally, there is the fact that Mario loses to Bowser and almost/kind-of dies in the opening minutes of the game, so there is the subtle feeling of a redemption arc throughout the game, of atoning for a previous failure.

| Paper Mario | |

| World | Home, Traditional/Recognizable |

| Connection to World | Significant, you are famous and well-known |

| Lore / Prophecy | None |

| Overworld | Expansive |

| Mechanics | Basic RPG Fighting Mechanics |

| Paper Element | Purely aesthetic |

| Stakes | Saving Peach, Restoring Peace to the Mushroom Kingdom, Restoring the Ability to Grant Wishes |

| Mario’s Connection to the Story | Personal |

| Villains who are not Bowser or His Minions | None |

| Presence of Supporting Characters | Expansive |

| Depth of Supporting Characters | Not especially so, not necessarily connected to the main plot |

| Idea of Love Saving the World | Minimal |

| Death? | No deaths (Twink is hurt, but he returns) |

| 3rd Act Twist? | None |

The Thousand-Year Door: A Familiar yet Different World with a More Complex Story

TTYD shifts the story, leaving some elements of what we expect from a Mario adventure but moving it slightly farther away from tradition. The Rogueport-hub-world where the action takes place isn’t /necessarily/ the Mushroom Kingdom, as it is not the grass/desert/ice/island worlds that we’ve come to associate with the Mushroom Kingdom. But it is clearly still close enough where Mushroom Kingdom denizens make it their home. The game contracts – slightly – as there is less overworld to explore, most new locations are accessible through less connected means like pipes, and pathways become more linear and left-to-right, but the storyline gets deeper.

Remember your core characters, for they are the franchise [1] – Mario, Peach, Bowser, and Luigi. Things start out and Mario and Peach are happy. She’s off travelling and feeling comfortable by herself but finds a treasure map and wants to share it with Mario. Meanwhile, Luigi, left at home again, decides to go on his own adventure and we feel his confidence growing slightly, even if his story in the Waffle Kingdom is different from Mario’s. Meanwhile, Bowser has very much officially LOST and is now looking for meaning (and spends the entire game searching for it, being one step behind the heroes and villains throughout).

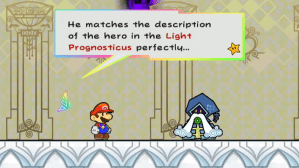

However, there is more world out there than the Mushroom Kingdom and we are introduced to the idea of prophecies and lore. Hidden treasures abound and there are theories of an ancient evil existing long ago. Additionally, it becomes clear that the people that are our main characters, specifically Mario and Peach, can be exploited. Mario is the great hero that the villains plan to manipulate into collecting all of the Crystal Stars to open the TTYD for them. And Peach, pure of heart, is used to open the chest containing the map and be a vessel for the demon.

The X-Naut villains have more depth, not necessarily beyond their roles in their evil plans (Grodus is not redeemed in any way, and neither is Crump), but in terms of the larger world. It is confirmed that even if there is “peace” among the Mario/Bowser/Peach faction temporarily, there are still other forces out there that are perpetuating nefarious activities.

The demon proves too powerful for Grodus so he cannot manipulate it, and the love that Mario got from helping all of these towns, as well as Peach, is used to quell the Shadow Queen from plunging the world into darkness. So there is a connection to the world as well as the main story plot, which moves slightly farther from the Mushroom Kingdom. Keep in mind, the Shadow Queen never mentions destroying worlds completely, she just wants everyone to be her slaves in darkness from a more elemental purpose. Not “lives will end,” but “lives will be far worse,” and this fear is greater than “oh no, the Princess is gone and wishes can’t be granted” from the original.

TTYD is somewhat Mario’s story, as his kindness towards Vivian and developing reputation in the worlds he visits shapes the A plot around him. Also, TTYD feels the most like Peach’s story, given her sideplot with TEC reflecting the themes and her pure-of-heart-ness trying to be exploited.

In general, in TTYD, the main characters (Mario, Peach, Bowser, Luigi) are at their most separated, with the game sending each one off on their own plotline, with these main characters barely sharing any scenes together, before bringing them all back together in SPM.

Supporting characters in the game like TEC, Vivian, and Bobbery have more in-depth character arcs and are more directly related to shaping the narrative plot, but there are still a lot of supporting characters like Pennington or Jolene or King K who have their own characterizations and arcs independent of the TTYD plot itself. In many ways, there are less named NPCs in TTYD than in PM64 (i.e. slightly less party members, less characters with repeated side quests), but the ones that are present typically have more character depth than the original.

Jolene’s completed arc (left), Pennington speaking aboard the Excess Express (right)

Gameplay-wise, though there is less overworld to explore in a connected way compared to the original, the battle mechanics at the base level are more advanced, with more choices to make in terms of partner strategy, more action commands to utilize when it comes to Special Moves, and more wild cards to think about in battle like the “audience” participation.

NOTE: In the following, red indicates a reduction, and green indicates an increase.

| Paper Mario | Paper Mario: TTYD | |

| World | Home, Traditional/Recognizable | Farther from Home, not fully the Mushroom Kingdom but with some Mushroom Kingdom denizens |

| Connection to World | Significant, you are famous and well-known | Somewhat, you are less well-known but come to be appreciated by the world |

| Lore / Prophecy | None | Yes – You have to stop the Shadow Queen from awakening |

| Overworld | Expansive in all directions, extremely connected | 3D but somewhat linear in terms of play space, less connected |

| Mechanics | Basic RPG Fighting Mechanics | More Advanced RPG Fighting Mechanics |

| Paper Element | Purely aesthetic | Aesthetic, but now with abilities to turn into different types of paper |

| Stakes | Saving Peach, Restoring Peace to the Mushroom Kingdom, Restoring the Ability to Grant Wishes | Higher – Saving Peach, but also Stopping the Shadow Queen from plunging the world into darkness |

| Mario’s Connection to the Story | Personal | Direct (Peach connection), but Impersonal (the villains are not after you in particular) |

| Villains who are not Bowser or His Minions | None | Yes (Grodus, Shadow Queen), but basic |

| Presence of Supporting Characters | Expansive | Slightly Less Expansive |

| Depth of Supporting Characters | Not especially so, not necessarily connected to the main plot | Many connected to main plot, slightly more depth |

| Idea of Love Saving the World | Minimal | Yes, on the fringes (Vivian-Mario, TEC-Peach, Bobbery-Scarlette, world’s love represented in the Crystal Stars against the Shadow Queen) |

| Death? | No deaths (Twink is hurt, but he returns) | Yes, on the fringes (Bobbery-Scarlette backstory, TEC is “shut down” and villain Grodus is killed by Shadow Queen, although both return in the post-game) |

| 3rd Act Twist? | None | Yes, Beldam was the mastermind. You don’t fight her after this reveal, but Peach is possessed and you do fight her |

Super Paper Mario: A Contracted, Unfamiliar World with the Deepest, Character-Driven Story

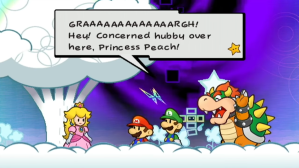

Then comes Super. Our core characters have now been very much established, and the action begins immediately with our characters thrust together. Bowser has reestablished his forces and wants to mount a new attack, but Count Bleck beats him to it. He forces Bowser and Peach into marriage (with Bowser gleefully accepting) and unleashes the Chaos Heart. Luigi, clearly far more confident than he was in the original, rushes to stop it, but it is too late, everyone is captured, and the Void begins to grow.

Oh dear – just like the X-Nauts, there are more beings out there who want to manipulate our characters and old prophecies to create harm on the world. Just like Grodus, who had Crump and the Shadow Sirens as his minions, here Count Bleck has Nastasia, O’Chunks, Mimi, and Dimentio. We can already see the game playing with established familiar tropes, but then shifting them.

Unlike TTYD, our heroes didn’t STOP the bad guys in unleashing an old prophecy in its infancy, like Mario defeating the Shadow Queen before she can wreck havoc on the world. The prophecy is well underway by the time the action starts.

Mario is sent to Flipside to find the Pure Hearts and reverse the prophecy, and Flipside feels far farther from the Mushroom Kingdom than we’ve ever been, at this dimensional nexus of worlds. There are no Toads to be found, no partners to obtain except for some thinly-drawn Pixls, no Mushroom Kingdom denizens who recognize you. This is true with the enemies you fight as well. Although some Goombas and Koopas exist, there are a lot of wacky, multi-colored enemies composed of arrays of creatively-drawn aesthetics, which only ever appear in this game. You are as far from home as you’ve ever been, and the stakes are at their highest. A world literally is erased in front of you in Chapter 6, so more than other game in the series, it is very clear on what will happen if Count Bleck wins.

The world in SPM is smaller in terms of its space and characters, but expansive in its scope. On top of that, the game is less interconnected than TTYD was, which in turn was less connected than PM64 was. Chapters are divided into four sections, and you frequently teleport in location from the end of one section to the start of the next section. Whereas PM64 had you accessing new locations using connected means like walking or train level, and TTYD often had you using pipes to do so with a handful of more connected means like trains, you access all new locations in SPM through interdimensional doors.

But this lack of physical connection ends up mattering less because of the way that the characters and themes begin to show hidden depth, connecting everything in a different way. By moving the action farther from the Mushroom Kingdom, SPM is satisfying multiple sequel tenets of not remaking the original and honing the focus onto the series’ main characters. New, but familiar [1].

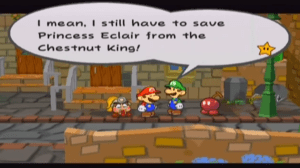

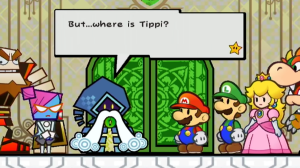

As such in the game, traditional expectations get subverted. There is an inter-Peach chapter after Chapter 1, and you wonder “oh my, just like the first two, I see a pattern repeating.” Nope, she gets mysteriously saved immediately and joins your party. This game isn’t about saving Peach. Bowser? You find him at the beginning of Chapter 3 and Peach convinces him, playing on their history that has now been built up, to join the party. Okay, this game isn’t about fighting Bowser. Luigi? He gets brainwashed into Mr. L, who you meet in Chapter 4, far from the hapless brother from PM64 and far from the trepidatious hero trying to have his own adventure in TTYD. Now, he’s your enemy. You need to save him, but the story isn’t about saving him, because it’s bigger than that.

In many ways, the first four chapters of the game explore the most traditional Mario archetypes (i.e. saving Peach, defeating Bowser, fighting each of the Big Bad’s minions) to tell you that this is game is about more than that. The first chapter itself combines the “traditional” Mario worlds (grass land and desert land) into one chapter to basically say “we are going to burn through what you expect from this game really quickly, to then explore what you do not.” And then after Chapter 4, the game starts subverting the high-level stakes themselves. The game first tells you what it isn’t, before revealing what it is.

The world reaches farther than ever in terms of unique locations, but has also shrunk in terms of its characters (and literally in terms of 2D space). Over time, more aspects begin to show depth. This is true of the Cragnon-Floro Sapien subplot in Chapter 5 and the Luvbi subplot in Chapter 7.

But most especially, this is true with the backstory between Blumiere and Timpani, and the realization that Blumiere was Bleck and Timpani is Tippi, your “guide” Pixl.

So, not only is there a progression across the three games from Goombario (more or less just a fan of you), to Goombella (someone connected to your guide on all of the lore), to Tippi (someone connected to your guide on all the lore – a.k.a. Merlon – but who also is the key to the plot’s backstory and theme), but now this deepens Bleck and removes any comparisons to Grodus.

You thought he was just another Grodus, leading a bunch of dark minions intent on exploiting prophecies and our characters to (this time) literally erase all worlds? Nope. He’s a man with a broken heart because Timpani was taken from him. The series’ most complex villain nailed at the very end, but there’s more!

In TTYD, Beldam (Grodus’s minion) is revealed to be the true mastermind and true servant to the Shadow Queen. In SPM, Dimentio is revealed to be the true mastermind and the true evil towards the Dark Prognosticus. In TTYD, these machinations release the Shadow Queen, who possesses Peach and becomes the final boss. In SPM, as Count Bleck is resigning himself to his own death in order to stop the prophecy, Dimentio takes command of the Chaos Heart and Luigi and literally merges with them both, becoming the final boss.

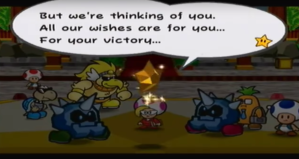

In the end, remaining villains AND heroes combine forces to defeat Dimentio. Unlike the previous two games, it is not the world’s love that restores the main MacGuffins (in this case the Pure Hearts) in the final fight – it is your party’s love for you and then the love/respect between Count Bleck and his minions that does the trick (which is also emblematic of the world contracting but deepening). The story is these 8 or so characters.

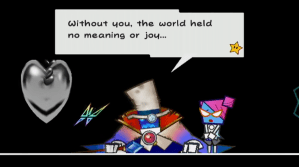

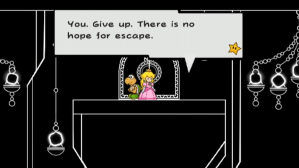

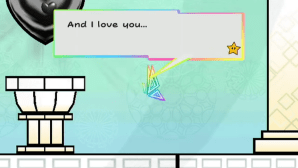

Afterward, with Dimentio defeated but the Chaos Heart still threatening to destroy all worlds, Bleck and Tippi renew their love, using love to banish the Chaos Heart and all those connected to the prophecy… including themselves. They thus sacrifice themselves to stop the prophecy and save all worlds.

So, in PM64, the story is Mario vs. Bowser. In TTYD, our main core characters are present fighting an old prophecy. In SPM, in truth, though our heroes are there fighting an old prophecy, it is really Count Bleck and Tippi who, in the end, are the ones shaping the story. The game uses Mario and the others to tell their story, getting closer to this central theme as the game progresses, and using the hidden complexities of both its main characters and thematic foils like Luvbi in order to do so.

The last chapter, Chapter 8, even feels like it has “curtain call” moments for these main characters of the story. Each section within the chapter ends with a member of your party (Bowser, then Peach, then Luigi) seemingly sacrificing himself or herself to save the rest of the party, and the game uses these moments to showcase the core character elements of both your party and the villains they fight.

Bowser fights O’Chunks to prove that he is the toughest guy around, and then, with a cave-in threatening everyone, continues to hold up the ceiling to prove that he is the toughest guy around. But he also is adamant about getting Peach out of the room safe, so we can see that Bowser, at his core, is a wannabe tough guy who hopelessly loves Peach. O’Chunks is also a wannabe tough guy, but he respects the “code” and therefore wants the heroes to succeed if they have beaten him.

Peach fights Mimi because Mimi insults her neediness of “boys.” But the Peach of the Paper Mario series is far more competent, so she has to fight for her dignity. But, even after winning, she can’t leave Mimi to die, because she is pure of heart, and lingers for too long, putting her life in danger when the floor collapses. So, Peach is a competent princess whose pure heart gets her into trouble. Mimi is a spoiled girl, but one capable of more than just tricks and who doesn’t necessarily know a whole lot of kindness, so is therefore surprised by Peach’s act of sacrifice.

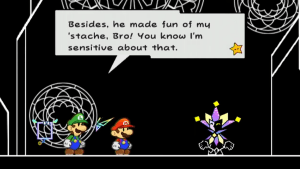

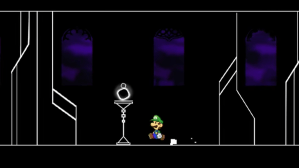

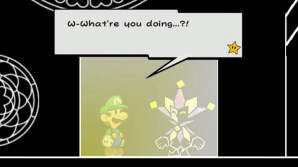

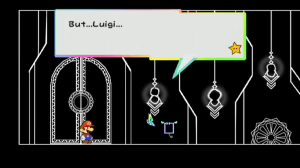

Luigi fights Dimentio so that the others won’t be lost in vain, but also because Dimentio insults his mustache, meaning that he also has an ego and a sense of worth that he feels he needs to prove. And, unfortunately, he doesn’t win, because Dimentio tricks him into getting close enough to knock both of them out. This suggests that someone like Luigi, who is naturally good-natured but has cripplingly low self-esteem and a need to prove himself, can be easily manipulated by someone like Nastasia, or especially by Dimentio who is a master manipulator without a heart at all.

There is a line in the final battle where Dimentio says that Luigi is, according to the prophecy, the “ideal host for the Chaos Heart,” and I’ve always thought about this line’s inclusion in the game. It could be just a throwaway line about prophecy, but it could speak to those hidden depths. Is the reason because he is a good person, but who also harbors a lot of repressed hurt and anger? Is this a warning to all of us on our potential to turn cruel, like Bleck did?

Luigi’s Nuanced Character Arc in Super Paper Mario

Again, though the last act sets up Mario to have a curtain call against Count Bleck, he… doesn’t. We already know who Mario is, he proved himself back in the first game. But the other characters are less clear. As the fight with Count Bleck progresses, your party returns, and the conflict becomes more about Tippi and Bleck than about Mario or anyone else. And after Dimentio’s attempt to take control, it is Tippi and Count Bleck’s sacrifice that is front and center.

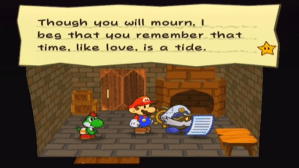

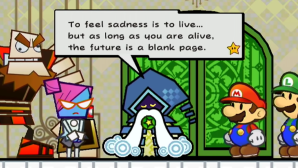

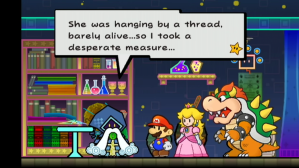

Finally, in the game’s denoument, the last two key characters, Merlon and Nastasia, get their “curtain call” moments, and who also serve as the closest audience surrogates for feeling the losses of Tippi and Bleck. Merlon, who saved the then-Timpani long ago when she was near death by turning her into a Pixl and then cared for her for some time, appears visibly distraught and gets a chance to make a speech about what loss means in a greater prophesied world. And Nastasia, who came to genuinely love Count Bleck over her time serving him, even though she knew he could never return it, cries over this loss while still attempting to remain hopeful for the future.

Additionally, it is worth noting that Merlon himself has a role in all three Paper Mario games. Though it is never confirmed if it is the same Merlon or multiple Merlons with the same name, this case of progression across the games is true with him as well. The Merlon in PM64 can give you directions in exchange for coins and serves as one key story beat, but mostly is a flavorful NPC who serves as comic relief due to his overlong stories. The Merlon in TTYD can power up your partners, and thus is more important to your progress and is someone you will visit far more than just once. The Merlon in SPM, who is the most important of these Merlon incarnations, serves as both your guide who knows about the game’s lore and as Tippi’s caretaker. He is a side character who, as early as PM64, is clearly not from Mario’s world and comes from somewhere far more ancient. And by SPM, he is at his most complex from a character perspective and most important from a game perspective. This speaks to a larger theme at play.

The progression of the Merlon character

As the three games progress, Mario’s world contracts and the larger world, filled with more lore, lore-related characters, and complex villains, expands and deepens. We’re not fighting for our home world anymore, we’re fighting for something greater. Unlike PM64, we are not going to get a parade. And unlike TTYD, it is likely that much of this universe will not even know that it was us who saved them. But that’s not what matters here. We’re not fighting for known denizens, we’re fighting for something more thematic and elemental. In the end, it is the complexities and conflicts of this world not familiar/known to us that determine the fates against the highest stakes of the series. That the resolutions to these complexities strike such an emotional chord speak of proof to how well-done the story was/is.

The game plays the resolutions for real. Yes, the series played with death in TTYD, first by having the TEC subplot, wherein he learns to love Peach and then is “shut down”. You do feel his death, but he is a side character. Though he does serve a thematic and plot-related purpose (i.e. echoing the nature of love as well as informing Peach that the villains plan to have the demon posses her), he is not playing a central role. The same is true with Admiral Bobbery’s backstory, where it is discovered that he turned his back on the sea because of his wife Scarlette’s ultimely death. This is backstory that isn’t impacting the central plot, but is touching on themes.

TEC’s shutdown (left), and Scarlette’s letter (right)

In SPM, Count Bleck and Tippi disappear and it feels like they genuinely died. And they are not side characters. Like TEC/Peach in TTYD, it is a love story. But the “deaths” here are the main center of the plot, which happen at the climax/denouement of the game, and it is far deeper.

Merlon’s quote in the last scene of the game- “To feel sadness is to live… But as long as you are alive, the future is a blank page” feels like a series thesis statement. Bad things happen to all of us – we lose people, we can be underappreciated like Luigi and feel sad as a result, we can feel heartbreak like Bleck has felt – but as long as we are alive, it is up to us whether we give in to our pain like Bleck did, or whether we get up and fight for each other and the world (like Mario did in the prologue of PM64, and like Bleck and Tippi do at the end of SPM).

The last frame of the story, after the credits, and the trilogy, is Blumiere and Timpani, in true form, walking down a hill together somewhere. Is it heaven? Is it a world they escaped to? Are they alive or dead? Who knows. We realize that this entire trilogy was a story of love. In PM64, it’s Mario’s love for Peach, Bowser’s twisted love for Peach, her love for Mario and the world, and the world’s love for the Star Spirits. In TTYD, there is love (and we see it form) between TEC/Peach, between Vivian towards Mario, or the past love between Bobbery and his wife, but there is also a love from the world towards you that helps save the day. In SPM, though all of these other loves are present, it is the love of these two seemingly “side” characters, your most advanced “guide” character, Tippi, and your most advanced villain, Count Bleck, that end up being the Strong Center of not just SPM but the entire series. It’s the frame the series chooses to end on after all.

Notice the progression of affection between the main series characters (i.e. Mario/Peach, Bowser/Peach in PM64), then to affection between main series characters and supporting characters (i.e. Peach/TEC in TTYD), and then to love between supporting characters (i.e. Blumiere/Timpani in SPM), but with each progression becoming more fleshed out, dynamic, and developed.

SPM isn’t really Mario’s story (save for a handful of moments when you save Tippi in the aforementioned Chapter 3 and she develops an affection for you). It isn’t really Peach’s story either, as she gets rescued early and then isn’t a driving force of the plot. However, it /is/ the culmination of Bowser and Luigi’s character arcs. And truthfully – the game isn’t meant to be Mario’s story. The game is Tippi and Count Bleck’s story, who personify the theme of the trilogy, and that’s ok.

And in the end, the series closes with an image of their love, and you realize that that is what all three games were about all along.

| Paper Mario | Paper Mario: TTYD | Super Paper Mario | |

| World | Home, Traditional, Recognizable | Farther from Home, not fully the Mushroom Kingdom but with some Mushroom Kingdom denizens | Farthest from Home, Very Unfamiliar |

| Connection to World | Significant, you are famous and well-known | Somewhat, you are less well-known but come to be appreciated by the world | Not especially, feels like you are passing through except for a few moments |

| Lore / Prophecy | None | Yes – You have to stop the Shadow Queen from awakening | Yes, already set in motion, character-driven – you have to undo the Dark Prognosticus set in motion by Count Bleck |

| Overworld | Expansive in all directions, extremely connected | 3D but somewhat linear in terms of play space, less connected | 2D with some 3D elements, blocky, not connected at all |

| Mechanics | Basic RPG Fighting Mechanics | More Advanced RPG Fighting Mechanics | Platformer, no Battle System |

| Paper Element | Purely aesthetic | Aesthetic, but now with abilities to turn into different types of paper | Aesthetic, and now with paper becoming a core mechanic of the 2D/3D flip, finding sides of the paper world you didn’t see at first |

| Stakes | Saving Peach, Restoring Peace to the Mushroom Kingdom, Restoring the Ability to Grant Wishes | Higher – Saving Peach, but also Stopping the Shadow Queen from plunging the world into darkness | Highest – Stopping the End of the World, Saving a brainwashed Luigi, and Restoring Count Bleck’s soul |

| Mario’s Connection to the Story | Personal | Direct (Peach connection), but Impersonal (the villains are not after you in particular) | Indirect (barely through Tippi), and Impersonal (the villains know of you only through lore) |

| Villains who are not Bowser or His Minions | None | Yes (Grodus, Shadow Queen), but basic | Yes (Count Bleck, Dimentio, Mimi, O’Chunks, Mr. L), and Complex |

| Presence of Supporting Characters | Expansive | Slightly Less Expansive | Significantly Contracted |

| Depth of Supporting Characters | Not especially so, not necessarily connected to the main plot | Many connected to main plot, slightly more depth | Almost all connected to main plot, significant and thematic depth |

| Idea of Love Saving the World | Minimal | Yes, on the fringes (Vivian-Mario, TEC-Peach, Bobbery-Scarlette, world’s love represented in the Crystal Stars against the Shadow Queen) | Yes, Literally |

| Death? | No deaths (Twink is hurt, but he returns) | Yes, on the fringes (Bobbery-Scarlette backstory, TEC is “shut down” and villain Grodus is killed by Shadow Queen, although both return in the post-game) | Yes, both existentially (destruction of Sammer’s Kingdom) and personally (death of Luvbi, and then Tippi and Count Bleck) – Central to plot and themes |

| 3rd Act Twist? | None | Yes, Beldam was the mastermind. You don’t fight her after this reveal, but Peach is possessed and you do fight her | Yes, Dimentio is the true mastermind, and you must fight him after he uses a brainwashed Luigi to take control |

Conclusion: What Could Have Been

Most people know that Super Paper Mario has one of the greatest Mario stories but has some mechanically flaws, but its nuances go deeper than that.

Are the overworld mechanics still a little irksome in SPM? Kind of. Until you realize that this entire story was slowly shrinking the play space from PM64 on to SPM in order to deepen the themes.

All three games “feel” like you are fighting to save the world, but only in the last game is the end of the world actually literal. The series’ mythos [1], as it is, is to collect MacGuffins that are based in lore and connected to a feeling of love, and to use them to defeat the Big Bad, but the series builds on it with each game. All three games “feel” like you need love to save the world, but only in the last game is that phrase absolutely and directly true.

While I still probably would hail TTYD as the best on its own, as that perfect blend of an expanded but familiar narrative along with that perfect blend of expanded mechanics… SPM is a gem in its own right and as part of a greater whole.

Once you realize the story it is trying to tell, once you see it as the culmination of a trilogy that deepens existing narrative and thematic threads, and once you can forgive it for its mechanics, you realize that SPM actually is an underrated masterpiece.

But again – to love the story, you have to forgive it for its mechanics.

If the entire series is shrinking the overworld space but expanding the details below, then, in going with that progression, Super Paper Mario should have the most advanced battle system. TTYD has a more condensed overworld space but a more advanced fighting system, so if that progression were to continue, SPM should be even more advanced. If the details at the basest level are at their most complex, narratively speaking, in SPM, then so should the mechanical system.

And because TTYD didn’t shrink PM64’s battle system, it feels jarring that SPM doubles back on that apparent progression set in motion by its predecessor. These mechanics are trying to “reinvent the wheel” when they did not need to [1].

The mechanics are not deeper, the gameplay action is not deeper. But everything else is.

I have read some reviews about how, if Super Paper Mario had been the first entry of a series, people would have been more forgiving of its mechanics, and that is probably true. There wouldn’t be a “this doesn’t feel like a Paper Mario game” feeling in terms of mechanics. However, in that scenario, the narrative elements of the game would feel like less of a pay-off, and the idea of Mario not being the driving force of the plot could have bothered some players. That’s the issue. Mechanically, the game feels like it should be the first entry of the series because of how trimmed down it is, or at least an entry of a series that isn’t Paper Mario. But narratively, it not only feels like Paper Mario, but feels like the climactic, culminating entry of the series.

Had this problem been fixed, people would have stayed with the game through the first few chapters before the characters’ (and worlds’) hidden depth is revealed. The first half of SPM is showing us our expectations of the game, before eventually subverting them, which is clever in its own right. Then, once this subversion takes place, you realize that all of the elements are there, just hidden at first. It’s just hindered by that initial feel of “wait… this isn’t a Paper Mario game.” And even after, when SPM’s story is at its greatest, there is still a somewhat jarring feel that the deepest story of the trilogy has the most simplistic fighting mechanics.

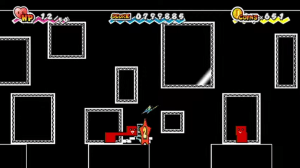

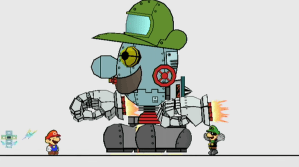

Super Dimentio is a climactic, narratively satisfying villain undone by fairly easy final boss mechanics

The game could keep everything else. Keep the 2D structure. Keep the ability for Mario to switch from 2D to 3D. Keep the somewhat simplistic Wii remote controls. Keep the Pixls as your party, because the story isn’t about 12 or so underdeveloped characters, it is about one very developed character in Tippi, and let the player figure that out.

But bring back the turn-based battle mechanics and make them advanced.

Have each Pixl be a mechanic that you can utilize. Allow the player to have two main characters (Mario, Peach, Bowser, or Luigi) out at the same time (or maybe even three, like Super Mario RPG did all those years ago, or even all four like Mario + Luigi: Partners in Time does). Maybe have different main characters utilize different special moves that they can use between each other, like the Mario + Luigi series does with the Bros. attacks. Make items require action commands in order to use them (which the game already employs), but have them be done so in a true RPG format.

Examples of more advanced RPG Battle Mechanics used in other Mario RPGs

Snoman Gaming’s video on the mixed elements of Super‘s design adds to this idea, suggesting the possibility that the 2D-to-3D flip be an in-battle mechanic, with some enemies’ defenses and weak points only being visible in 3D [4].

This way, there wouldn’t be any instances of a narratively rich boss character being defeated without any time to breathe. The theme of deepening the most micro-elements of the story would carry over to the gameplay. The game would start off marginally simplistic, but at least feel like Paper Mario, and grow more emergently complex in tune with the rest of the narrative themes. Every sequel tenet would be fulfilled [1], and all of the progressions built up in the first two games would pay off.

In my original post on TTYD, I stated that I was still waiting for that one Mario game that combined every one of its narrative elements to create the perfect story. Rumor has it that a new Paper Mario game is in the works for the Nintendo Switch, and, according to these rumors, it is being based off of the original two games. Though I am ecstatic about these rumors of a new Paper Mario that will be, in theory, more akin to the original, Nintendo doesn’t need a new game for that story to exist, because it already does. All Nintendo has to do is remaster Super Paper Mario with deeper, turn-based mechanics, and the rest would be history. It already could have been.

NOTE (Updated 5/17/2020): These rumors have since become crystallized, with the newly released trailer of Paper Mario: The Origami King, and, first thoughts on the game feel… mixed. The game looks like it has the first original plot since Super, and it indeed carries the potential of a deeper, darker story. However, it’s hard to call it “based off of the originals,” because the mechanics and battle system still seem experimental. In this case, it very much feels closer to Super than it does PM64 or TTYD: it feels like a game with a potentially deep story and experimental mechanics.

This further speaks of Super‘s role in the Paper Mario lineage. Had Super had the mechanics to fully support its story, it is likely that fans would feel like the original trilogy was paid off in full, and would be more accepting of more experimental titles in the series, but that is not the case. Fans have been clamoring for that new game that returns the series to its roots, because the series never got that third entry that followed-up TTYD and paid off the progressions set up by the series. Super could have, and did, from a story perspective, but it didn’t from a gameplay perspective. That is why fans are still fervently waiting for a game that does.

NOTE (Updated 1/2/21): I have since written a full-length analysis on Paper Mario: The Origami King, and why it actually checks off a lot of the boxes we have been waiting if we were to genuinely give it a chance.

Super Paper Mario not only could have been the deepest game-supported story of the Mario lineage in its own right, it also could have been the perfect culminating entry in a trilogy of game narratives, and that is not a chance that Nintendo will get to utilize anytime soon. Even if Nintendo releases the perfect next Paper Mario game with all of the restored gameplay elements discussed above and a deep story in its own right, it cannot pay off all of the progressive narrative elements that Super Paper Mario already paid off perfectly thirteen years ago.

I read another pro-Super Paper Mario article written by Caroline Delbert stating that the world of SPM is “huge and ambitious,” and that, by this point, “the world had stretched until its parts no longer hold” [5]. And this is true. SPM is an extraordinarily ambitious game with genuine, heavy stakes, with its world and narrative complexities condensed but stretched to their limits. She asks, “Where could Nintendo and Intelligent Systems have taken this series next?”

The answer – they really couldn’t. They couldn’t expand the world, stretch its characters, and condense its narrative to its core any more than SPM does. On top of that, upon release, many fans were quick to disregard the entire game because of the mechanics, thus subliminally telling Nintendo that they didn’t want game-mechanic experiments interfering with a Paper Mario story. So, Nintendo jettisoned story wholeheartedly in Sticker Star and Color Splash, gave fans what they wanted (turn-based battles), but left room for their own creative experimentations (remember: one cannot ask game designers to not experiment at all). If you look at Sticker Star and Color Splash like this – as creative, spin-off experiments – and not as series canon, you can appreciate them a little more.

See, SPM is not a perfect game. But by being overly critical of what we got, Nintendo stopped trying to blend story with mechanical tweaks. There wasn’t a whole lot of longform story left to tell anyway, but it is likely that Nintendo would have tried to incorporate some sort of shortform story into subsequent Paper Mario games had fans been less vitriolic of SPM.

The fact remains, however. Any new Paper Mario game likely will stand alone. Any new Paper Mario cannot increase the stakes any higher than SPM. Any new Paper Mario cannot condense its narrative to its base theme (true, sacrificial love can save the world) any more than SPM. A new Paper Mario can tell its own shortform story, blend the Mario structure with some clever dialogue and a deep plot, but it cannot be the series-capper that SPM is.

And like SPM itself asks us to do with its themes, one has to look at the game with a nuanced lens. It is far better to accept SPM for what it is than to dismiss it.

But the basic conclusion, simply stated, is this: Super Paper Mario is a great game… that could have been perfect.

If the gameplay mechanics had supported its deepening progression, SPM would simultaneously have the best interconnected game narrative from both a short form and a long form perspective.

And SPM, not TTYD, would be the one we’d all still be talking about.

[1] Ken Miyamoto, The Ten Commandments of Writing Great Sequels, Screencraft 2015, https://screencraft.org/2015/10/02/the-ten-commandments-of-writing-a-great-sequel/

[2] Snoman Gaming, Good Game Design – What Makes a Great Sequel? (Paper Mario TTYD), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPvEGVL0ouI

[3] Resonant Arc, Paper Mario 64 Review, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lxy1-8ZXUo&t=3s

[4] Snoman Gaming, Bad Game Design – Super Paper Mario & Color Splash, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JvjmgnLTKKQ

[5] Caroline Delbert, Super Paper Mario is a Flawed Masterpiece, Dec 3 2018, https://medium.com/@cdelbert/super-paper-mario-is-a-flawed-masterpiece-e749da54b604

The Rest of My Mario Narrative Series

The Greatest Mario Story Ever Told (and Why It Still Isn’t Perfect)

Challengers to Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (Expanded)

Deep Analysis of Super Paper Mario: A Nature of Order Applied to a Complicated Narrative

Paper Mario: The Origami King – Give it a Chance to Make an Impact

On Nintendo’s Nostalgia-Based Model

The Super Mario Bros. Movie (YouTube Review)

Additional Analysis

The Controversy of Super Paper Mario – Nintendrew, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=euZscfTm1qU

What Makes Super Paper Mario A Paper Mario – SuperMarioT, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7LZ9jamwFg&t=415s

Super Paper Mario: The Best Story in the Mario Franchise? – ZoopTheRat, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lMhp6Toh0Y

For Fun

Super Paper Mario Musical Bytes – Complete Package – Man on the Internet, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Fm1Teu2cY&t=8s